|

Unlike passenger coaches, freight and express cars did not always follow set routes through downtown Cleveland. Routes varied as necessary, and an exact accounting of where cars moved at any particular time would be extremely difficult, if not impossible. However, there were some general practices and patterns. Originally, the "trolley freight ordinance" of 1913 had limited freight trains to certain hours of the night. This restriction seems to have been lifted at some point by the 1920's, as photographs and records of daytime freight trains do exist. The three car limit was also eased for nighttime movements, with some trains pulling as many as five trailers through the streets. The much anticipated subways were never built, and it's possible the city relented on some restrictions, perhaps resigned to freight in the streets as a fact of life. Freight cars generally tried to avoid the tight curves and heavy traffic of Public Square and other busy streets. Therefore, the "standard" westbound route made a meandering trip around the south side of downtown. From the freight terminal the route went south on East 9th street, west on Central Ave. (now Carnegie Ave.), across the 2800 foot long Central Viaduct over the Cuyahoga River to West 14th Street, west on Abbey Ave. to Lorain Ave., then north on West 25th Street, rejoining the passenger route on Detroit Ave. After the subway entrance to the Detroit-Superior bridge was built on West 25th, interurban freight turned on Franklin Blvd., to Dexter Place, and West 29th to Detroit Ave. (CSW cars continued on Lorain Ave. to West Park.) This route was disrupted several times, especially during excavation of the railroad approaches to Cleveland Union Terminal (CUT). From July 1925 to the spring of 1926, Abbey Ave. was closed while a bridge was built for the west CUT approach. The Central Viaduct was closed to traffic from October 1927 to January 1929 while the east CUT approach was built. Interurban traffic was again blocked in 1930 when the Central Viaduct received deck repairs. During these periods freight trains were forced to use the Detroit-Superior bridge, following Ontario north to Superior, or avoiding Public Square by following East 9th to St. Clair, West 3rd, and Superior. The resulting traffic problems caused city council to consider banning daytime freight trains once again, but a compromise was struck allowing freight except during rush hours. Southbound traffic to Akron was free of most difficulties, simply following the Cleveland Railway's Broadway line to Miles Road and then onto private right-of-way. The CP&E had the slowest route to contend with, running on city streets (Euclid or St. Clair) as far east as Willoughby. Transition in the 1920's By the middle of the 1920's interurbans were feeling the pinch caused by the increasing popularity of automobiles. Ridership and revenues were declining, and those lines which had never been particularly profitable or stable were hit the hardest. Both lines of the former EOT were abandoned by April 1925, and the CP&E closed on May 20, 1926. Even the once robust Cleveland Southwestern was faltering, forced to reorganize and abandon some routes in 1924. Despite hardships, the LSE and NOT&L remained viable, but a clearly recognizable shift was occurring as freight became a nearly equal priority to passengers. Both companies continued to build and purchase additional freight motors and trailers. By 1926 they jointly leased yard space at the Cleveland Railway's East 34th Street station, just south of the Kingsbury Run viaduct, to facilitate interchange of freight cars and train crews. Surviving freight logs from the period attest to not only the amount of freight the LSE was moving, but the plethora of interline shipments. It has been suggested that the LSE hosted more "foreign" freight equipment than any other Midwest interurban, regularly interchanging motors from NOT&L, Eastern Michigan-Toledo, Lima-Toledo, and others. Trailers from railways across Ohio and neighboring states became daily visitors, including Toledo & Indiana; Toledo Fremont & Fostoria; Columbus, Delaware & Marion; Detroit United Railway; Michigan Electric; Toledo, Bowling Green & Southern; Western Ohio; Penn-Ohio; Dayton & Western; United Traction; Indiana Service Corporation; and Indiana, Columbus & Eastern. The LSE usually kept a wood box motor at Eagle Ave. to switch trailers and shuttle them between locations such as East 34th Street or freight sidings near Wagar Road in Rocky River. A tiny, single- truck switch motor, originally used to move coal cars at the Beach Park power house, was also reassigned to switch trailers at Eagle Ave. after the power house burned in 1925. Electric Railways Freight Co. To more efficiently handle all this freight, and help counter the ever increasing competition from trucks, the Electric Railways Freight Company (ERF) was organized on November 1, 1928. Closely modeled on the Electric Package Agency, ERF handled customer solicitation, billing, collections, interline agreements, and door-to-door pickup and delivery for its parent railways, the LSE, NOT&L, Penn-Ohio, Toledo & Indiana, and Ohio Public Service (formerly the Toledo, Port Clinton & Lakeside.) Service and schedules were carefully tailored to the needs of shippers in hopes of securing every last possible dollar of income. The ERF also had its own trucking subsidiary named Elway Transit (the name was supposedly a contraction of Electric Railways) to perform local pickup and delivery, and provide highway shipping in areas where connecting interurban lines had succumbed to bankruptcy and abandonment. Even at this late date, more terminal space was needed. Two historically significant buildings on the south side of Eagle Ave. were repurposed for use as freight house and ERF office space. The Belle-Vernon -Mapes Dairy Company had relocated to Carnegie Ave. earlier in 1928, and their Eagle Ave. milk plant was converted to the Lake Shore's inbound freight terminal. The second EPA depot of 1911 then became the LSE outbound terminal. The building adjoining the old milk plant had an even more interesting past. Built by the Anshe Chesed congregation in 1846, it had been the first synagogue in Cleveland. It was sold in 1906 and used as a wagon factory for many years before being leased by the ERF. Rail sidings and a dock were added to the east side of the building but its exterior appearance remained unchanged, albeit severely aged, standing testament to its former life as a temple. A small outbound freight house was also established at the Cleveland Railway barns on Madison Ave. in 1929 to take advantage of the manufacturing industries concentrated in that area. It was most likely reached by LSE cars via Clifton Blvd. and West 117th Street. The high water mark for LSE freight was reached in 1929, amounting to $894,000, 48% of all revenue. Unfortunately, that percentage was as much a result of declining passenger receipts as it was increased freight. New Partners Developments continued in 1930 which must have given at least a sense of cautious optimism. On January 1, 1930, a new interurban was born. The Cincinnati & Lake Erie was the creation of Thomas Conway Jr., possibly the most dedicated electric railway executive of the time. He dreamed of building an interurban between Cincinnati and Toledo, and also saw the earning potential of freight. On March 8, 1926, he purchased the decrepit Cincinnati & Dayton Traction Company, renamed it the Cincinnati, Dayton & Hamilton, and spent over a year completely modernizing its rolling stock, power equipment, and operations. Later he acquired the Indiana, Columbus & Eastern, and the Lima-Toledo, and merged them into one new company. He stunned the interurban industry by purchasing 15 new steel freight motors, an audacious move for the times, but one that would help make the C&LE a strong partner of the LSE. May 1930 saw the start of overnight freight between Cleveland and Fort Wayne, Indiana over the LSE, C&LE, and Fort Wayne-Lima Railroad. Bonner Railwagons An especially notable attempt by ERF to improve efficiency was the Bonner Railwagon. Invented by Col. Joseph Bonner of Toledo in 1898, the system was an early forerunner of the "piggyback" service adopted by railroads decades later. The wagons or trailers (originally horse-drawn, later pulled by motor trucks) could be used on streets conventionally, then loaded on a railway car for long distance travel. The trailers had wide-spaced wheels and no cross axles, and were parked astride the railway tracks on small ramps. A specially designed rail car was then run underneath them. Pneumatic jacks lifted the trailer wheels off the ramps slightly and clamped them securely in place. The transfer from road to rail could be accomplished in as little as four minutes. The system promised great efficiency and cost savings as high as 50% by eliminating the re-handling of freight between trucks and rail cars. Nor would cars have to sit idle waiting to be loaded or unloaded. The LSE began investigating the potential of the Railwagon system in 1928, and took delivery of a prototype rail car and a single trailer in July 1929. Licensing negotiations with Col. Bonner, however, ground to a standstill until August 1930. Commercial service with the Railwagons began September 1, 1930. Transfer points were located at Glendale yard outside Toledo and Beach Park outside Cleveland. The trailers were then trucked into the city to avoid paying local streetcar companies for track usage. The service was heavily promoted by ERF and so successful that in January 1931, Fred Coen proposed creating a subsidiary specifically to operate 61 Railwagons and 19 rail cars over the LSE, C&LE, NOT&L, Penn- Ohio, and Eastern Michigan-Toledo. Unfortunately, no immediate action was taken, and within months the LSE would lose almost all of these important connections. Daily Cleveland-Toledo Railwagon service continued into late 1932, when it clashed with the Public Utility Commission's rules on motor carrier certificates. The LSE appealed but lost, and then gave up on the endeavor. Beginning of the End Despite the peak of freight in 1929, and some hopeful signs in 1930, the sun was already setting on the interurban era. Just as automobiles were decimating passenger service, the rapidly accelerating loss of connecting railways was sounding the death knell of freight. The Michigan Electric Railway shut down in 1929, cutting off destinations beyond Detroit. The LSE purchased 14 box trailers from Michigan Electric and soldiered on. The next two losses were much closer to home and more painful. On July 1, 1931, the NOT&L ended freight service. Ironically, the NOT&L was still doing a large amount of freight business, despite competition from trucks. But the depression was putting pressure on both the interurban and freight shippers, and the holding company which owned the railway decided to concentrate on commercial power generation instead of transportation. The demise of NOT&L also denied the LSE connections with the Penn-Ohio and all the cities and towns south and southeast of Cleveland. Without these connections the ERF's reason for being evaporated, and the joint company was dissolved in August. The Cleveland Southwestern, which had been fighting a slow, losing battle for survival since 1924, reached its end in January 1931, when it asked the Public Utilities Commission for permission to abandon rail service. The Southwestern's freight depot was demolished a short time later and the vacant land used as a parking lot. The Western Ohio and the Fremont & Fostoria, which had comprised the Lima Route, ended on January 15, 1932. The Fort Wayne-Lima railway ended June 30, 1932. The Eastern Michigan-Toledo, successor to the Detroit, Monroe & Toledo, ended its precarious hold on life on October 4, 1932. Within only four short years, nearly the entire interurban network, which had transferred freight across four states, was gone. By 1934 the C&LE was the Lake Shore's only remaining freight partner. The LSE itself was declared bankrupt on January 30, 1933, as it was unable to pay millions in bond issues that had become due. Fred Coen was appointed the receiver and was determined to continue rail service as long as possible. Freight and the EPA were both still solvent, even if LSE and C&LE cars were the sole visitors at the once bustling Eagle Ave. depot. Business staggered on as best it could. Even more troubles arose when the Central Viaduct, on the main freight route, was condemned on April 4, 1935. The LSE compensated by arranging a long route even further south of town on Broadway, across the Kingsbury Run Viaduct at East 34th, then to Pershing and across the Clark Viaduct to either West 14th or West 25th, then on to Detroit Ave. Such detours complicated freight movements for the LSE and annoyed residents along the routes. Worse yet, the rickety, fifty year old, Kingsbury Run Viaduct was declared unsafe for interurbans only three weeks later. LSE freight cars were then completely cut off from Eagle Ave. Rail operations were moved to the dis-used Cleveland Electric yard at East 34th Street. The Eagle Ave. terminal remained open, but all freight had to be shuttled by truck between there and East 34th Street. Retired passenger combine 16 was moved to the East 34th yard for use as an office and crew bullpen. The Cleveland Electric Railway came to the rescue of the LSE by building a freight depot next to the Rocky River car barns, which was completed on August 1, 1935. The LSE had to pay rent, and all freight still had to be trucked from Eagle Ave., but they were spared the headache of the long, makeshift, street route through Cleveland. |

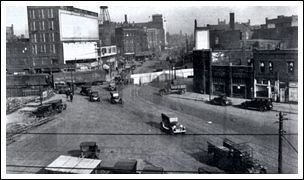

freight through such traffic was out of the question. (Charles Goethe) |

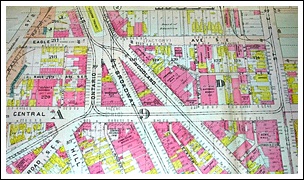

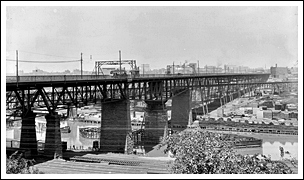

and the Central Viaduct (lower left) was much more practical. (Drew Penfield) |

|

was 2800 feet long with a swing section over the river. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

a trailer north on Ontario St. during Central Viaduct closure. (Cleveland State University) |

|

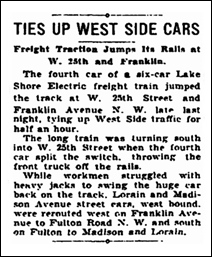

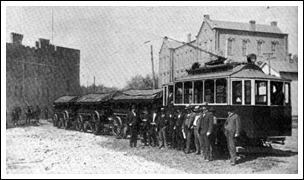

long as six cars were sometimes operated on the streets at night. (Plain Dealer) |

|

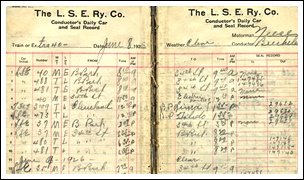

and the many "foriegn" cars hauled by the LSE. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

equipment regularly interchanged with the LSE. (Richard Krisak) |

|

Electric Railways Freight Company. (John Rehor) |

|

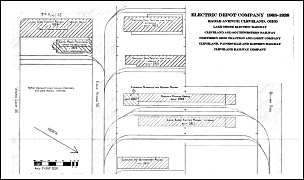

of freight service, circa 1929. (Jim Mihalek) |

|

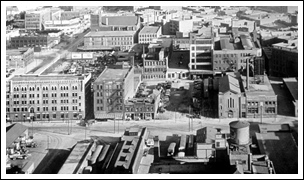

atop the Caxton Building. Click photo to see labels. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

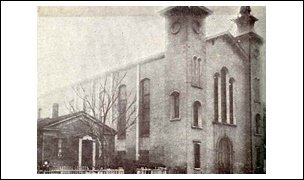

19th century, long before it became the ERF depot. (B'nai Jeshurun) |

|

the Electric Railways Freight depot. (Tom Bailey) |

|

Business was quite good on this day in the late 1920's. (Tom Patton) |

|

Eagle Ave. sometime in 1931. (Drew Penfield) |

|

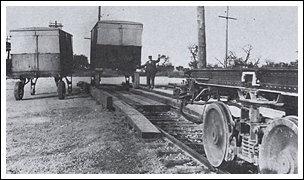

horse-drawn wagons in Toledo in 1898. (Electrical Engineer) |

the specially designed flat car using low ramps. (George Krambles) |

including the Bonner Railwagons. (Dennis Lamont) |

waiting to be scrapped in Sandusky, May 22, 1938. (Dennis Lamont) |

of the Southwestern's milk dock. Freight house was replaced by a parking lot (far right) in 1931. (Ralph A. Perkin photo) |

a major blow to LSE freight. (Plain Dealer) |

trailers at depot, and autos where Southwestern depot stood. (Ralph Perkin photo) |

37 and trailer 489, circa 1933. (Tom Bailey) |

cars at the ERF depot. Missing dock and broken windows suggest depot has been abandoned. (Tom Bailey) |

Eagle Ave. in the early 1930's. (Dennis Lamont) |

River freight house in January 1937. (Dennis Lamont) |

Transit truck trailer at right. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

|

|