|

Cleveland's center of interurban freight for many years was a group of depots just off East 9th Street between Bolivar Road and Eagle Ave. The full story of the Lake Shore Electric's freight business, however, is far more complex and encompasses various locations and several other railways. Although freight was a very minor aspect of the interurban business during its rapid growth at the beginning of the 20th century (passenger service was lucrative and in high demand, and therefore the priority) it would become the primary source of revenue during the precarious struggle for survival in the depression years. Specifically, "freight" referred to quantities of wholesale goods and large items requiring special handling and facilities. In contrast, "express" consisted mainly of packages and individual items which were often carried in the baggage compartment of combine cars. The U.S. Postal Service did not offer Parcel Post service until 1913, therefore most packages were shipped by private express companies - the era's equivalent of UPS or FedEx. In the early years, interurbans followed the steam railroad practice of contracting with companies such as American Express, Wells Fargo, and United States Express, to handle the logistics, pickup, and delivery, while providing little more than over the rails transportation themselves. The railroads, always hyper-sensitive to the threat of competition, attempted to deny interurbans the right to carry express, freight, and mail, through a lawsuit in 1899 (Ohio v. Dayton Traction Co.) The court ruled for the interurbans, and while some did offer freight service (LSE predecessor the Toledo, Fremont & Norwalk was one) the majority carried only express. Electric Package Agency At the end of the 1890's, Cleveland was emerging as the national leader in electric railways. In addition to the network of city streetcar lines, new interurbans were connecting the city center with small towns and rural villages in all directions. The three biggest railways - the Akron, Bedford & Cleveland (predecessor of the Northern Ohio Traction & Light); the Cleveland Painesville & Eastern; and the Lorain and Cleveland (predecessor of the Lake Shore Electric) - were all controlled by the Everett-Moore syndicate, but each railway had their own contracts with express companies. In June 1898, the syndicate investigated the possibility of establishing its own subsidiary to handle express and baggage, and by the end of July the Electric Package Agency (EPA) had been formed. Officers of the new company included Barney Mahler, secretary of the Lorain & Cleveland Railway; Abraham Lewenthal, an attorney and Mahler's soon to be son-in-law; and Charles Kenworthy, an Akron native with extensive experience in the express business. Establishment of the EPA did not make any big ripples in either the railway or express business. Some voiced doubt that it could be successful, citing failed attempts by steam railroads to operate their own express agencies. But the EPA planned to offer faster service and lower rates, and set a precedent by announcing that they would cover the one cent per package Spanish-American War tax rather than charging it to their customers. The package agency's first office was at 143 Seneca Street (now the site of the justice center on West 3rd), inside the Merchant's Delivery and Storage Company. Packages and baggage were accepted for shipment here, with Merchant's Delivery presumably providing pickup and delivery (drayage) to homes and businesses. This arrangement was probably intended to be temporary, to test the feasibility of the EPA without making a large investment. By November the EPA had placed ads looking to buy their own horses for express wagons, and on December 1 1898, the company moved to a storefront at 92 Ontario Street, just north of the Society For Savings building on Public Square. Business increased further in 1899 when the Cleveland, Elyria & Western Electric Railway (forerunner of the Cleveland Southwestern) joined the EPA. The new location, however, was still a far cry from a proper freight terminal. No sidings or platforms existed, and all cars had to be loaded and unloaded in the street. Unsightly and haphazard piles of cargo often blocked the sidewalk, while stopped cars impeded traffic. In July 1900, the situation prompted one city councilman to formally ask the city law director whether the railways had any right to use the streets for handling freight and express. The law director reported back that the railways were indeed acting within their rights, but it was obvious to all that the EPA had outgrown its home. A committee representing six interurban companies and the Cleveland Electric Railway was formed to address the problem in March 1901. It recommended a single union station to handle both passengers and freight for all electric railways. In May, the interurbans formed the jointly owned Electric Depot Company to build and operate such a terminal. A site on East 9th Street, between Bolivar and Eagle, was selected and purchased for $75,000 on July 11. Most of the houses occupying the site were cleared in August, sidings were laid, and work on the new depot was expected to begin shortly thereafter. However, construction was delayed some months for reasons that remain unclear. Coincidentally, around this time, word leaked to the press that Everett-Moore was formulating plans to "invade the freight business" and compete directly with steam railroads on a large scale. Construction of the depot may have been delayed so the design could be modified to accommodate freight on a larger scale. In January 1902, however, all plans for the union terminal and expanded freight service were put on hold indefinitely. The Everett-Moore syndicate found itself overextended and unable to repay its loans. The press politely referred to the situation as an "embarrassment," the creditors remained friendly, and the syndicate's finances were put under the control of a banker's committee to oversee reorganization. Expenditures for a new terminal and the cars necessary for freight service were out of the question. The depot site remained vacant, used only by AB&C and LSE passenger cars on layover. A month before Everett-Moore's "embarrassment", three of their interurban lines (the Cleveland & Eastern; Cleveland & Chagrin Falls; and Chagrin Falls & Eastern) were merged to form the Eastern Ohio Traction Company. The territory of this railway was primarily farms southeast of Cleveland, stretching into Geauga and Portage counties. With little direct competition from steam railroads, or any other reliable transportation, the EOT made full freight service an integral part of operations from the very start. For the first time, farmers in the region were able to easily ship their produce and milk to Cleveland, and receive all manner of goods from the city daily. The EOT shipped everything from fresh baked bread to farm machinery, and even hauled cars of coal and other freight from steam railroads. But the biggest commodity by far was milk. In 1902 the EOT delivered 3000 gallons of milk to the city every day, and was hauling more freight tonnage annually than all other Cleveland interurbans combined. Although not a member of the EPA, the EOT depot was located next to the EPA on Ontario Street. All the shortcomings and hardships of that location were magnified for the EOT due to the large volume of freight it handled. New Depot Desperate for better facilities, the EOT pushed for an off-street freight depot of its own at the East 9th Street property. In June 1902, a frame house on the site was converted to an office and a small, sheet iron freight station with its own spur was built at the rear. While the buildings themselves were not large and intended to be temporary, the off- street location was an enormous improvement. In December 1902, the ambitious plan for a combined passenger and freight depot was officially scrapped. A passenger waiting room would be opened between Euclid and Superior Avenues, nearer to the shopping district and the property at East 9th and Eagle would be used for freight only. Plans were scaled back even further in February 1903, when it was announced that the Lake Shore Electric was ending the freight service it had inherited from the Toledo, Fremont & Norwalk Railway. Freight was proving uneconomic without investing in new cars and facilities. Instead the LSE would carry only EPA express. Relief from the horribly impractical situation on Public Square finally materialized that summer. On June 21, 1903, architects Searles & Hirsh awarded a contract to the Skeel Brothers construction company to build a new express depot within sixty days. The sturdy brick and sandstone building was 28 feet wide and 267 feet long. The north end, facing Bolivar, was an ornate two-story office building to house the express agent, clerk, cashier, auditor, and other offices. The single story "express shed" extended nearly to Eagle Ave. and featured thick wood plank flooring, steel overhead doors along both sides, and a seven foot wide platform for loading and unloading interurban cars. Skylights, electric lights, and white paint, all combined to make the interior bright. The official opening took place on the night of August 29, 1903, when a grand banquet was given by EPA president Barney Mahler. Nearly 100 guests, mostly officials of the company and EPA agents from across the system, enjoyed an elegant dinner in the newly completed and brightly lit warehouse. Live music was provided by the popular Rosenthal's Orchestra. Speeches and toasts were made by Barney Mahler, Charles Kenworthy, Abe Lewenthal, Edgar Hyman, and M.W. Weiner of the EPA, F.T. Pomeroy of the Cleveland Southwestern, and Frederick Coen of the Lake Shore Electric. The EPA was starting to realize its potential - able to implement fast, efficient, express service to all points on both member and connecting railways. Traffic agreements were made with lines connecting to the Northern Ohio Traction & Light at Akron, as well as the Cleveland & Buffalo and Detroit & Cleveland steamship lines and the Detroit United Railway. Points as distant as New Philadelphia, Ohio and Flint, Michigan could exchange shipments via the EPA. Same day service was possible as far west as Toledo. Rates were based on the hundredweight (100 pounds) and distance. For 75 cents, the highest rate, one hundred pounds could be shipped 120 miles from Cleveland to Toledo over the LSE in about seven hours. Additionally, the EPA gave a 10% discounted rate to ship fruit, poultry, eggs, and produce, from farms in the surrounding countryside to markets in Cleveland. Ten men were employed at the depot, 9 teamsters performed pick-up and delivery in Cleveland, and 25 other agents and teamsters were employed in towns along the railway routes. The Cleveland depot became a hive of activity, with horse wagons on one side, freight motors of the various railways on the other, as well as passenger cars on layover and combine cars taking on loads of baggage and express before moving to the passenger terminal to begin their runs. Interestingly, there are at least three documented instances of the EPA shipping horses in this period. The first apparently took place in 1902, when several horses were transported from Norwalk to Cleveland. In October 1903, the LSE shipped twenty horses from Lorain to Sandusky. And exactly one year later, the NOT&L shipped a carload of horses quickly and comfortably from Akron to Cleveland. Shipping livestock never became a regular occurence, however, the only other notable instance being a carload of race horses shipped by the LSE from Lima to Rockport in 1916. Milk Service Technically, the EPA did not handle milk shipments. Due to the different amount of milk shipped from each territory (the Cleveland Southwestern hauled far more milk than did the LSE, for example), the usual profit sharing arrangement of the EPA was deemed unfavorable. Milk was hauled in the same cars as EPA express, but the costs and profits were borne entirely by the individual railway. In early years the milk was transferred to wagons at various locations, usually at the city limits. This changed due to another development at Eagle Ave. Effective July 1, 1903, the Belle Vernon Dairy Company merged with the Mapes Brothers Dairy. The resulting company, Belle-Vernon-Mapes, was large enough to need a central processing plant and wholesale distribution center, which they planned to build at 706 Eagle Ave. The decision to locate the milk plant here was not coincidental. Congressman Jacob Beidler, president of the Belle Vernon Dairy, was also vice president of the CP&E Railway, and therefore directly involved with Everett-Moore and the EPA. The EOT was already hauling the largest volume of milk in Cleveland, and with the opening of the new EPA depot, freight cars of all interurban lines would be converging on Eagle Ave. Exactly when the new milk plant opened is unclear, but it was probably sometime in the first half of 1904. Around this time the EOT's original, temporary freight shed disappeared, replaced by a platform for unloading milk cans. EOT freight was then handled from the south end of the EPA depot, although the two companies continued to operate separately. Milk was still transferred to other customers at other locations, but a great deal of it went to Belle-Vernon-Mapes. By 1906, interurbans were hauling 10,000 gallons of milk daily, and Belle-Vernon-Mapes was supplying over 25% of all the milk sold in Cleveland. |

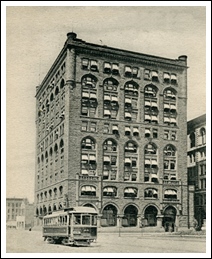

played a part in the evolution of the freight business. (Street Railway Review) |

one of Cleveland's interurbans at the turn of the century. (Drew Penfield) |

|

Cleveland Electric Ry. and instrumental in creating the Electric Package Agency. (Drew Penfield) |

|

at 143 Seneca (West 3rd), between St. Clair and Lakeside. (Drew Penfield) |

|

shipments by the 1898 War Revenue Act. (1898revenues.blogspot.com) |

|

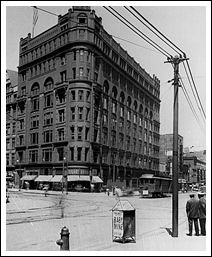

The small building in the background would become the second EPA location in 1898. (Drew Penfield) |

|

in 1899. The Old Stone Church is in background. (James Johnson) |

|

Everett-Moore's "embarrassment" in 1902. (Plain Dealer) |

|

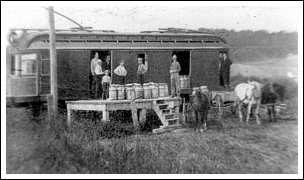

amounts of milk from the many farms along its route. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

Chardon branch to ship their milk to the city. (Cleveland & Eastern Historical Society) |

|

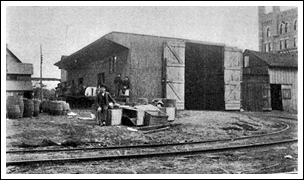

East 9th Street and Eagle Ave. in 1902. (Electric Railway Journal) |

|

Toledo and Norwalk in 1903, and shipped only express for many years. (Cleveland Plain Dealer) |

|

Bolivar Road. Warehouse section is at rear. (Electric Railway Journal) |

(Electric Railway Journal) |

was transferred between wagons and electric cars. (Dennis Lamont) |

and the tagged milk cans stacked on the platform. (Dennis Lamont) |

loading dock around 1904. (Dennis Lamont) |

a Barney & Smith freight car in the early days. (Dennis Lamont) |

wagons at various locations, as seen here. (Cleveland & Eastern Historical Society) |

Brothers Dairy in 1903 to become Belle-Vernon-Mapes. (Drew Penfield) |

probably for the Belle-Vernon-Mapes processing plant. (Dennis Lamont) |

(Drew Penfield) |

Wellington over the Cleveland Southwestern. (Dennis Lamont) |

over the Cleveland Southwestern. (Dennis Lamont) |

EPA depot, probably around 1905. (Bill Volkmer) |

southbound on East 9th St. at Euclid Ave. (Drew Penfield) |

TF&N in 1901) at the Eagle Ave. depot in 1903. (Electric Railway Journal) |

rebuilt from a passenger coach for express duty. (Dennis Lamont) |

urban Guide lists cut-off times for shipments to various towns. (Dennis Lamont) |

the age of 45 in 1908. He was succeeded by Edgar Hyman. (Plain Dealer) |

|

|

|