|

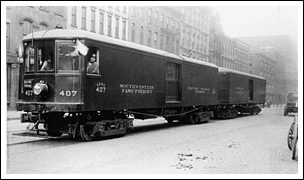

The interurbans continued to prosper throughout the decade, and the EPA grew accordingly. Only three years after opening the Eagle Ave. depot, the EPA had 40 wagons, 53 agents in various cities and towns, and employed 14 messengers who rode the cars and sometimes delivered packages personally. The LSE operated four westbound EPA cars daily, with a box motor leaving for Toledo at 9am, Norwalk bound cars at 4pm and 8pm, and a fourth from Fremont to Toledo. Additionally, the 1pm Toledo limited combine picked up express at the depot before boarding passengers at Public Square. The same number of cars made eastbound trips to Cleveland, and on Sunday a car delivered bundles of newspapers as far west as Norwalk. By 1910 business had increased to the point that the EPA employed 200 men and was outgrowing its facilities once again. On May 20, 1911, architect Willard Hirsh let the contract for a second depot to be built adjacent to the first. The George B. McMillan Co. took the job and the depot was completed by December, less than 90 days from the beginning of excavation. The building was very similar to the first in size and appearance, but with important differences in construction. Built entirely of reinforced concrete and brick, and featuring a sprinkler system, it was claimed to be "absolutely fireproof." (The first depot also received a sprinkler system at this time.) The floor was a reinforced concrete slab five inches thick, tested to a load of over six hundred pounds per square foot. Below this was a basement for storing delivery vehicles, accessible by concrete ramps at either end. The first depot was then used exclusively by the EPA, while the new depot was shared between the EPA, the Cleveland & Eastern, and Cleveland, Youngstown & Eastern (two lines which had been created when the struggling EOT was split up in 1910.) The milk business was also handled at the new depot, as the old milk dock on the site had been removed. Trolley Freight Ordinance Even before the new depot was committed to paper, the interurban lines were being lobbied to expand freight service. As early as January 1911, the wholesale merchants board of the Chamber of Commerce was asking for carload and less-than-carload (LCL) freight service, positioned as a happy medium between the cheap but slow steam railroads, and the fast but expensive EPA express. A slightly discounted rate was already available for some goods, especially farm produce, but still too expensive and unprofitable for many shippers. Cleveland merchants argued that such freight service would increase their sales by thousands each month while providing new revenue for the railways. By the end of 1911, all Cleveland interurbans had agreed to a trial of the service. A reduced rate was made possible by foregoing many of the conveniences that express included (drayage, additional insurance, looser packaging restrictions, and COD collection.) Carload freight remained problematic because of the Tayler Grant. This settlement, enacted in 1910, had ended the war between the Cleveland Electric Railway and Mayor Tom Johnson over private vs. municipal control of streetcar service. Under the grant, Cleveland Electric operated the service, but all rule making and rate setting authority lay with city council. One such rule was the prohibition of hauling freight trailers within the city. A carload freight service would therefore require the impractical arrangement of a motor car for each shipment. An amendment to the Tayler Grant that would allow the interurbans to operate freight trains in the city was proposed in December 1911, but met with immediate opposition. Mayor-elect Newton Baker called freight service on city streets a 'nerve racking, noise making, public nuisance.' Residents living on the west side routes and along Clifton Blvd. in Lakewood also opposed the amendment, holding public meetings and circulating petitions. A clause in the amendment which allowed for the hauling of bulk freight such as carloads of coal, stone, and iron, was also a serious point of contention. Proponents cited the increase in trade that would result for Cleveland merchants and manufacturers, and the reduced cost of produce shipped from the farming regions. E.F. Schneider, general manager of the Cleveland Southwestern, stated that in the area around Florence and Berlin Heights, 300-500 carloads of apples and other fruit was available annually, but often went to other cities via steam railroads. Interurban service would allow fast-ripening fruit to be delivered to Cleveland markets quickly and cheaply, without the need for refrigeration. Retailers in nearby towns could place orders with Cleveland wholesalers in the morning and have their goods by the afternoon. What steam railroads took days to ship could be done by interurbans in hours. The debate raged in city council, citizen meetings, and newspaper editorials for two years, often framed as "a question of community good against personal inconvenience or discomfort." Changes were made to the amendment, such as striking the clause allowing bulk freight, and eventually even mayor Newton came to support it. On November 4, 1913, the "trolley freight ordinance," as it became known, was approved by voters. Three car freight trains (including the motor car) were permitted to operate on city streets between the hours of 3am-6am and 8pm-10pm. The new ordinance had little immediate effect, however, because none of the interurban lines had any freight trailers to haul. But the door was open and the railways set about making interline agreements and tariffs and ramping up their LCL service. Interurban freight in Cleveland was clearly growing, but still accounted for a small minority of the total receipts. Between 1911 and 1913, annual freight revenue of the LSE increased 32%, from $86,467 to $114,158, or 10% of all income. Passenger revenue increased 7.5% in the same period. Through service to Detroit and Lima opened June 18 and August 2, 1911, respectively, offering additional connections for express and freight. Cleveland was also pushing forward with an ambitious subway plan in an effort to relieve congestion on surface streets. In fact, the "trolley freight ordinance" which allowed freight trains in the city, stipulated that all freight would have to enter through the subway once the system was operational. Between the subway plan and projected growth, the Electric Depot Company saw the strategic value of securing as much additional property as possible while it was available. In July 1910, two lots on the corner of Eagle and East 9th were purchased and the houses razed. In January 1913, four additional lots, constituting 235 foot of frontage on the north side of Eagle Ave., were purchased for $125,000. With this, the company owned more than 500 continuous feet of frontage on Eagle Ave., from East 9th Street west to the new Eagle School. Fast Freight The Cleveland Southwestern & Columbus became the first of the interurbans to inaugurate true freight service and operate trains on October 2, 1916. A great deal of effort went into the preparations which included converting older passenger cars to box motors, building freight trailers, and erecting 13 freight depots across the system. Members of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce spent two weeks promoting the new "Fast Freight" service to businesses in towns along the railway. Rates were set 25% higher than on steam railroads, but merchants were willing to pay a premium for fast delivery. Freight received anywhere on the system by closing time in the afternoon would be delivered by daybreak the following morning. Two carloads, totaling 40,000 pounds were shipped the first day and business increased 50% a month for the first few months. The Southwestern's Cleveland freight house was built at the corner of Eagle and East 9th. It was 36 x 140 feet, constructed of hollow tile and brick, and included office space and a double-track siding. The car roster at the start included five box motors and six trailers, with several more under construction at the Elyria shops. Two trains were operated out of Cleveland each day. The first departed at 5am, made local stops en route to Seville and Wooster, then returned to Cleveland at 3:50pm. The second departed Cleveland at 7pm bound for Bucyrus, setting out cars at Ashland and Mansfield. After arriving in Bucyrus at 2:50am it would layover until the return trip at 5:20pm, pick up Ashland and Mansfield cars, and arrive in Cleveland at 2:30am. This long haul train was capable of pulling four to five trailers once outside Cleveland city limits. The Southwestern's freight service reached Columbus and points beyond in September 1918, by way of the Marion-Bucyrus Railway, and the Columbus, Delaware & Marion Electric Railway. Overnight Cleveland to Columbus "hotshots" ran for the next 13 years, and were possibly the longest lived and most profitable interline freight movements of any Midwestern interurban. Despite the example set by the Southwestern, the other Cleveland railways were still slow to fully embrace the freight business. The Lake Shore's fleet of box motors, used primarily for express, milk, and baggage, numbered only five: three Barney & Smith cars inherited from the TF&N in 1901, and two others rebuilt from early passenger cars in 1907. In 1916 the LSE placed an order for its first serious freight motors, two 60 foot steel cars from the Jewett Car Company. Each had four 140 horsepower motors, and were the first LSE freight cars capable of pulling multicar trains. Although the LSE had no trailers of its own at this time, they did begin to haul trailers from connecting railways. The first car arrived in 1916, but construction of the second was delayed and was not delivered until December 5, 1918. Interestingly, these would be the only two freight motors the LSE would ever buy new from an outside builder. War Pushes Freight The United States' entry into World War I was a major impetus for the advancement of electric railway freight. Demands of the war effort, combined with a shortage of rolling stock and inadequate facilities, caused such crippling congestion on the steam railroads that they were nationalized in early 1918. It was realized that interurbans were well positioned to relieve the steam railroads of short haul and LCL freight. In May, the NOT&L began hauling food and war supplies 24 hours a day between Canton and Cleveland. E.F. Schneider, Fred Coen, and other Ohio railway officials visited the United States Railroad Administration in Washington D.C. to request government loans similar to what the railroads were receiving. They were turned down on the basis that while the steam railroads were under direct government control the electrics were still privately owned. Next, they asked permission from the Public Utilities Commission to increase passenger fares and freight rates in order to cover rising operating expenses and purchase additional freight equipment. The armistice came before the interurbans were able to ramp up their freight service enough to have much impact on the war effort, but the seeds were sown and began to germinate. Business of the EPA continued to grow in the meantime. New connections to Conneaut, Erie, and Buffalo opened on April 15, 1918, (although these never resulted in significant business), and five cars per week were making overnight deliveries to Detroit. On September 1, 1919, express service was extended to Warren, Niles, Girard, and Youngstown, over the NOT&L, Cleveland, Alliance & Mahoning Valley RR, and Mahoning & Shenango Ry. Apparently, this increase in business necessitated more space. In November 1918, the EPA signed a five year lease for the first floor and basement of a building at 704 Woodland Ave. The exact use of this location is unknown. The LSE finally announced the beginning of through freight service between Canton and Detroit on February 14, 1919. On September 1, service was extended to Youngstown. Ironically, a good deal of this freight was for the automobile industry. Tires and other rubber products were shipped from Akron to Toledo and Detroit, and finished autos were hauled back. NOT&L motors and trailers were the primary equipment used at this time, but the LSE began building its freight roster in earnest. Rather than purchase new or even second hand cars, the LSE took the unusual step of constructing many of its own cars in the shops at Sandusky. Between 1918 and 1920 they built six box trailers, three wood box motors, and three steel box motors. These early trailers featured end doors that allowed for easy loading/unloading of automobiles. Apparently, the shops could not produce trailers quickly or economically enough to meet demand and 14 more were purchased from the Cincinnati Car Company in 1920. (Eventually the LSE roster would include 65 box trailers.) The NOT&L commenced its full freight service on April 1, 1922. The company was somewhat skeptical at first, but became thoroughly convinced when monthly earnings reached $8000 after only six months. By the end of the year equipment was running at full capacity, and orders were placed for two new box motors and twelve more trailers. By January 1923, more than 100 cities throughout Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, and Pennsylvania were receiving overnight freight from the interurban network, and connections were possible to many more. EPA express continued over the same network. Additional Depots This surge in business naturally required another expansion of the depots on Eagle Ave. About a month before opening their freight service, the NOT&L built a new 25 x 175 foot freight house at 725 Eagle, on the property the Electric Depot Company had purchased in 1913. The railway's initial skepticism is evidenced by their choice to build a wood frame depot at the relatively low cost of $5000. But just as their rolling stock reached its limits quickly, so too did the freight house. In 1923 a second depot was built alongside the first, this one a substantial 40 x 160 foot brick and concrete structure with a two story office section at the front. A three track siding could accommodate at least nine cars. The first building was then designated as the inbound freight house and the second as outbound. The Cleveland, Painesville & Eastern began overnight freight between Cleveland and Ashtabula on December 1, 1922 in conjunction with the other railways. A 40 foot addition was built on the south end of the first EPA depot to house this operation. |

was signed on May 20, 1911. (Plain Dealer) |

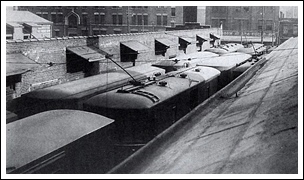

depots in 1912. Note the ramp to underground parking. (Electric Railway Journal) |

|

(Northern Ohio Railway Museum) |

|

second EPA depot, possibly around 1913. (Northern Ohio Railway Museum) |

|

freight was approved by voters on November 4, 1913. (Plain Dealer) |

|

years (marked in red) to prepare for future expansion. (Drew Penfield) |

|

Weideman Company wholesale grocers on West 9th St. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

the corner of East 9th and Eagle in 1917. (Electric Railway Journal) |

|

CSW freight house. Note the milk cans inside the box motor. (Bill Volkmer) |

|

shops, pulls a box trailer through the streets of Cleveland. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

urbans could help relieve railroad difficulties during WWI. (Plain Dealer) |

|

Conneaut, Erie, and Buffalo in 1918. (Plain Dealer) |

|

states at its peak in 1920. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

steel cars the LSE ordered from Jewett in 1916. (Ralph A. Perkin) |

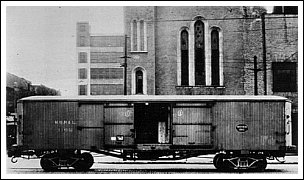

Note the end doors for loading automobiles. (Drew Penfield) |

(or rebuilt) at the LSE's own shops in 1920. (Dennis Lamont) |

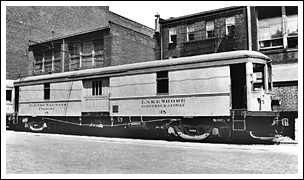

1920, such as car 38, which still exists. (Dennis Lamont) |

Agency to those of steam railroads. (Electric Railway Journal) |

(Drew Penfield) |

outbound at left, sometime in the busy 1920's. (Northern Ohio Railway Museum) |

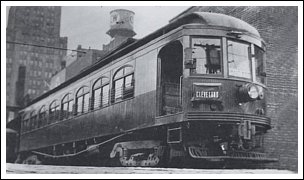

leave the freight house with a three car train, circa 1923. (James Blower) |

later photo with the Northern Ohio Power & Light name. (Dennis Lamont) |

cars in 1922-23 and leased them for shipping milk and meat. (Electric Railway Journal) |

most likely some of the fourteen ex-Michigan Railways cars purchased by the LSE in 1929. (Dennis Lamont) |

in the baggage compartment. (Dennis Lamont) |

after it began freight service in 1922. (Dennis Lamont) |

depots. Notice the Western Ohio "Lima Route" trailer. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

|

|