|

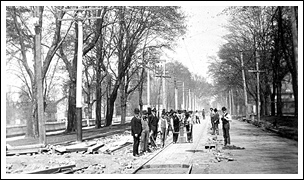

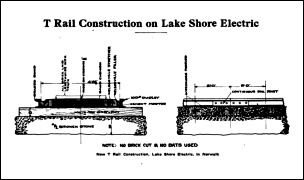

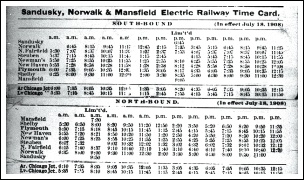

Management was not the only area seeing changes in 1907. Patronage of all the interurban lines was increasing steadily, with an attendant increase in car traffic. More track space was acquired on East Main Street by double-tracking from downtown to the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad crossing, approximately ⅗ of a mile. The following year, the existing track on East and West Main streets was rebuilt. The original girder rail laid down in 1893-94 was replaced with new 100 pound T-rail and special "nosed" brick paving. Expansion of a much bigger kind occurred in 1907, and would eventually have a major effect on Norwalk's position within the operation of the LSE. As early as October 1905, the LSE considered building a northern shortcut west of Sandusky that would shorten the distance between Sandusky and Toledo by more than twenty miles. This shortcut would also tap a new territory of potential riders and accommodate the large summer crowds that traveled to the popular and growing resort of Cedar Point. The Sandusky, Fremont & Southern Railway Co. was incorporated to build the line in 1906. Local traffic over the new route began on July 21, 1907, and after sufficient ballasting and final improvements, limited cars began running September 17 - the same day as Furman Stout's funeral. The overall number of limiteds was increased to six daily, each way, on a two hour headway. Cars alternated between the new "northern" division through Sandusky, and the "southern" division through Norwalk. Shuttle service ran between Ceylon Junction and Fremont opposite the limiteds. Thus, despite half the limiteds using the northern division, traffic through Norwalk actually increased. A further increase in traffic came from the Sandusky, Norwalk & Mansfield, which had reached Shelby and made its connection to Mansfield in early 1908. The first scheduled interline service in LSE history began July 11, 1908 between Mansfield and Sandusky, a distance of fifty-five miles. Round trips were made daily to give the people of Mansfield and the small towns along the SN&M an opportunity to enjoy a day at Cedar Point and return home the same evening. An LSE car operated by an SN&M crew departed Mansfield every morning at 7:30 and arrived in Sandusky at 9:50. The return car left Sandusky at 6:45 PM and arrived in Mansfield at 9:05. This schedule ended on Labor Day but was revived in some capacity for the summers of 1909-1911. Newspaper reports say that the LSE negotiated to purchase the SN&M in 1907. Even if true, nothing came of the negotiations, and the SN&M continued as an independent company. Setbacks The immense growth, expected to catapult Norwalk into the ranks of, if not beyond, its larger neighbors, never materialized. There was no catastrophic fall; Norwalk simply settled into its place as a modestly sized manufacturing city. Growth continued, but it never fulfilled the grand visions that had seemed a certainty only a few years before. There were, however, several setbacks in these years which almost certainly undermined the city's potential. Norwalk had expected to reach the stars on the rocket of the steel industry, which had come to town in 1901. In December 1907, the Norwalk Steel & Iron Company merged with the William Kavanaugh Manufacturing Company to become American Steel & Iron. Only a month later, however, the company went into receivership. This caused the immediate failure of the Ohio Trust Company of Norwalk, and indirectly the Norwalk Savings Bank. The president of the Norwalk Savings Bank was William Henry Price, who was also vice-president of the LSE. Price had a long and successful career in Norwalk real-estate and co-founded the bank in 1889. He was an early and large stockholder of the Sandusky, Milan & Norwalk railway, as well as a director of the company. His influence was at least partially responsible for the change of route in 1893 that placed the SM&N on Old State Road, where Price lived. When the Lake Shore Electric was consolidated in August 1901, both Price and his long time business partner C.H. Stewart were made directors. The Norwalk Savings Bank was a rare and unfortunate failure in Price's otherwise successful career, after which he moved to Lakewood to be closer to his Cleveland business interests. Despite the steel company and bank failures, business continued largely as usual. American Steel & Iron struggled on through 1908, fighting lawsuits for fraud and collusion, and was declared bankrupt twice more by 1910. The plant was then leased to the Crucible Steel Company of America, which operated at modest output until 1929. The presence of steam railroads in Norwalk also dramatically waned in these years. The Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad, once the city's largest employer, consolidated its disperse repair shops into one giant new facility at Collingwood, east of Cleveland, in 1903. Part of the Norwalk roundhouse was retained for emergency repairs, but the rest of the locomotive and car shops were taken over by the G.S. Stewart furniture company, which then became Norwalk's largest employer. A few years later the LS&MS expanded its Sandusky division into a four track mainline, capable of carrying far more freight and fast passenger trains than the single-track Norwalk division. By 1911 even the small emergency repair facility was closed. A true disaster struck the city in the early morning hours of August 24, 1908, when a fire destroyed nearly all of the Wheeling & Lake Erie railroad shops. The fire is believed to have started by spontaneous combustion in the blacksmith shop, where it was discovered around 5:00 AM. The fire department soon arrived but was thwarted by insufficient water pressure. Despite heroic efforts, the buildings containing the blacksmith, machine, boiler, and carpenter shops, storehouse, and offices were reduced to smoldering rubble within an hour. Only the roundhouse and coal tipple remained. Property damage was estimated at $300,000, but insured for only $5,000. Four hundred men, mostly skilled mechanics, were left jobless. The Reflector called it "the worst blow the city has ever received in its history." Initially, the Wheeling committed to rebuild the shops if Norwalk would raise $50,000. Residents and the Chamber of Commerce quickly raised the funds, but the city and the railroad could not agree on final terms. Soon after, the Wheeling relocated all major repair operations to a site near Massillon, where the north-south and east-west mainlines crossed. It was incorporated as the town of Brewster, Ohio in 1910. The Norwalk roundhouse was retained as a minor repair shop, but the Wheeling would never again have such a prominent presence in the city of its founding. Norwalk had always been a logical location for the LSE offices, being the midway point between Cleveland and Toledo. With the opening of the Sandusky, Fremont & Southern, however, Norwalk's position within the LSE was usurped. Sandusky was the mid-point on the new northern division, which quickly generated more traffic than Norwalk. It was also the location of the LSE's main repair shops, and the city's local streetcar routes required constant attention from management. Thus the LSE offices moved from the Case Block in Norwalk to the Stone Block on Columbus Avenue in Sandusky on April 15, 1909. At the same time, the LSE station moved from the Case Block to the former Norwalk Savings Bank at 12 East Main Street. Second Interurban Boom Despite these setbacks, Norwalk remained a strong town and continued to contribute to the flourishing interurbans. The years 1911-1913 are sometimes called the "second interurban boom." Unlike the frenzy of speculation and construction at the turn of the century, the second interurban boom was characterized by expansion and improvement of established railways and connections between them. The national economy had rebounded from the Panic of 1907, allowing interurbans to invest in new construction and improvements at a time when automobiles did not yet constitute any serious competition. The network of electric railways throughout Ohio and neighboring states was coming into full bloom. In the preceding years, the LSE had streamlined and upgraded its power system to a truly first-class standard. Abundant power allowed more traffic and kept the cars running reliably on schedule. Luxurious new cars were also purchased in this period. Twenty-five cars were purchased from the Niles Car Company in 1906-07 and became the backbone of the LSE's long distance limited service. Furman Stout had helped determine the specifications of the cars which included the first practical multiple unit (MU) electrical equipment, allowing two and three car trains to be powered by a single trolley pole and operated by a single motorman. The right-of-way was improved by replacing several wooden bridges between Lorain and Norwalk with steel and concrete, and some culverts were also widened and otherwise reinforced. Limited service on "The Lima Route" began in 1911 with the completion of the Fremont & Fostoria, linking the LSE with the Western Ohio railway. Cleveland - Detroit limiteds began operating the same year. By 1913, ridership and revenue was at all time highs. In addition to the local, limited, and express cars of the three lines that served the city directly, limiteds interchanged with the Western Ohio and Detroit United Railway also passed through on their way to and from Cleveland. One-hundred and twenty five cars rolled through town daily, a figure touted in advertisements from Norwalk's Chamber of Commerce. LSE 101 remained the only car dedicated to Norwalk city service, but photos prove cars from Sandusky occasionally showed up on Main Street as well. These were probably added during especially busy times, such as the Firelands centennial celebration in 1909, or substituted while car 101 was being maintained or repaired at the Sandusky shops. Given the volume of traffic, the safety record during the period was admirable. Accidents were few and far between, and those that did occur were relatively minor. On September 17, 1913, a limited and a local car collided near Brown's Curve, just west of the city where the track crossed from one side of the highway to the other. Thirteen people were injured. A much more spectacular, yet injury free, crash occurred on the morning of October 18, 1915, when a Lake Shore & Michigan Southern steam train struck a limited on East Main Street. Westbound car 7090 from the Detroit United Railway had just begun crossing the steam railroad when the rear truck became firmly lodged in the derail. The crew was unable to free the car under its own power and were alerted by the LS&MS flagman that a fast mail train was due any minute. The passengers were calmly evacuated with time to spare and watched from a distance as the steam train, unable to stop in time, smashed into the wood interurban car. The Lake Shore's Norwalk franchise expired in December 1917, twenty five years after it was originally granted to the Sandusky, Milan & Norwalk. The cars continued to operate without a franchise for two years as the city and the LSE negotiated terms. A new twenty five year franchise was granted December 31, 1919, and it appeared the next quarter century would continue much the same as the previous quarter. But the second interurban boom had already begun to wane, and the first serious cracks became apparent by the early 1920's. Early Decline Naturally, the smallest and weakest lines were the first to succumb to the changing times. The Sandusky, Norwalk & Mansfield never stood a chance of living up to the dreams of its founders. Despite the summer excursions to Cedar Point and freight car interchange with steam railroads, the little railway suffered from a lack of riders in the farmland it traversed and an incompetent, often absent management. The previously strong relationship with the LSE seems to have soured around 1912. The interline limiteds to Sandusky had ended due to lack of demand, and the SN&M was reportedly delinquent on payments to the LSE for its power supply when receivership came in 1912. The company began purchasing its power from the Cleveland Southwestern, and in 1913 the SN&M moved from the ticket office it shared with the LSE and joined the CSW across the street. It emerged from receivership in 1914, but went back under in 1917. In 1920 the railway again fell behind on its electric bill to the CSW, which was having its own troubles. After six months of non-payment, the CSW was unwilling to support to poverty-stricken line any further, and announced it would cut off the power at midnight on March 24, 1921. The last car ran that day, with former LSE motorman James Trimmer at the controller. (Trimmer returned to the LSE where, seventeen years later almost to the day, he again ran the last car over an interurban.) The SN&M property lay idle for many months until purchased and re-opened as the Norwalk & Shelby Railroad. The new company attempted to sidestep the problem of buying electric power by operating two gasoline powered rail cars built by the Elyria Foundry & Machine Company. They began running December 28, 1922, but the inherent weaknesses of the territory, and the business in general, brought it to a final end in the spring of 1924. Unsettlingly, the ailment spread to stronger members of the industry. The Cleveland Southwestern went into receivership on January 21, 1922. In some respects the Southwestern also suffered from territories of low patronage. Although business was still strong in and around Cleveland, and the fast freight service was a success, many cities along the road never grew to match the prosperous commercial and industrial centers that the Lake Shore was fortunate enough to serve. The seeds of its fate, although slow to germinate, had been planted in 1901 when the LSE bought the TF&N and locked up the Cleveland-Toledo route. The Southwestern continued operations but began to prune its unprofitable branches. On October 30, 1923, receiver Frank Wilson admitted that the company could not compete with the faster LSE and asked the Public Utilities Commission for permission to abandon the Norwalk branch west of Oberlin. The LSE considered buying the Southwestern's more direct and level right-of-way between Norwalk and Berlin Heights, believing they could utilize it to improve their own service. An opportunity they had missed in 1901 when they rebuffed Fred Pomeroy's offer to share the route. The purchase never took place, however. Perhaps the LSE decided it was not a cost effective move. The last Southwestern car to visit Norwalk ran on November 7, 1923, leaving the LSE as the sole interurban in Norwalk. But the most formidable competition was still warming up. Rubber Meets the Road John Ernsthausen came to Norwalk in 1912 and later was co-founder of the Norwalk Produce Company, which purchased eggs, milk, and other produce from local farmers, then shipped them to Cleveland for re-sale. Ernsthausen claimed the interurban schedules were unreliable, and turned to a number of local independent truck drivers. (Curiously, this claim contradicts nearly all other information on interurban express and freight and was not the experience of other farmers who consistently shipped their produce by electric railway..) In 1923, the independent truckers agreed to sell their equipment to Ernsthausen and become regular employees, and Norwalk Truck Lines was born. Not only were the trucks taking Norwalk's farm produce business from the LSE, but trucks returning from Cleveland also began hauling all manner of regular freight. Soon after, the produce side of the business was dropped and Norwalk Truck Lines expanded further into the general freight business. The LSE was expanding its freight service as well that year. Ten additional freight trailers were purchased from the Kuhlman Car Company of Cleveland, new freight houses were built in some towns, and existing ones, including Norwalk's, were enlarged. Despite competition from truck lines, freight became a more important segment of interurban revenue through the 1920's and helped keep the LSE alive in the 1930's. As if private automobiles and freight trucks weren't enough of a thorn in the side of interurbans, buses also became serious direct competition just as the jitneys were being regulated out of existence. The Norwalk Bus Company was founded in 1924 by Frank Adelman (a Norwalk merchant, former policeman, and automobile enthusiast) and H.C. Newman (a Norwalk Oldsmobile dealer and taxi operator.) Their buses began running between Norwalk and Mansfield on October 30, filling the void left by the anemic Sandusky, Norwalk & Mansfield and its hopeless successor the Norwalk & Shelby. In December 1924, the company set its sights on the LSE and asked the Public Utilities Commission for a certificate to operate their buses between Norwalk and Sandusky. The LSE vehemently protested, arguing that they were already servicing the route sufficiently, and it appears the commission agreed. This victory was tempered, however, when the Lake Shore's Michigan partner, the Detroit United Railway, was put in receivership the following March. The rubber tire competition kept coming. In September 1926, the Detroit-Toledo-Cleveland Bus Co. applied to operate busses between its namesake cities via Norwalk, and in December the Cleveland-Elyria Bus Co. sought an Elyria to Fremont route through Norwalk. Even in more profitable days, interurbans were never flush with surplus. But as the 1920's roared on, controlling costs became a significant concern for the LSE, especially in light of the fierce new competition. One cost-cutting measure was a switch to local streetcars that could be operated by a single motorman rather than a motorman and conductor. Norwalk's antiquated city car, in service since 1898, was finally replaced in December 1925 with a single-truck Birney car acquired second-hand from Baltimore's United Railway's & Electric Company. Numbered 115, it was put under the command of Norwalk's own Fred Gassman, who had worked the Main Street car since 1906. |

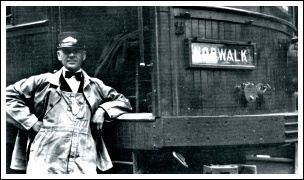

on West Main Street in 1908. (Dennis Lamont) |

(Electric Traction Weekly) |

|

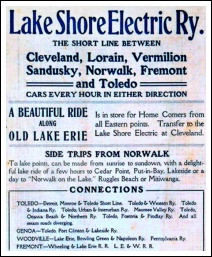

emphasizing the easy access to resorts along the LSE. (Plain Dealer) |

|

daily between Sandusky and Mansfield that summer. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

on July 17, 1908. View is north at Benedict and Main. (Drew Penfield) |

|

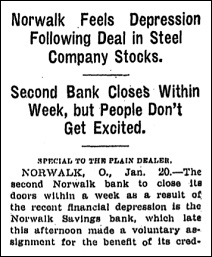

two Norwalk banks in January 1908. (Plain Dealer) |

|

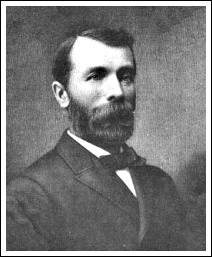

Savings Bank, a director of the SM&N, and a director and vice-president of the LSE. (Drew Penfield) |

|

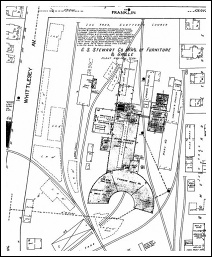

the G.S. Stewart furniture company after the railroad left Norwalk. (Drew Penfield) |

|

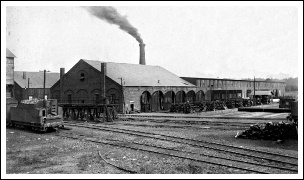

in August 1908, only days before being almost completely destroyed by a fire. (F.D. Foster photo) |

|

fire of August 23, 1908. (F.D. Foster photo) |

|

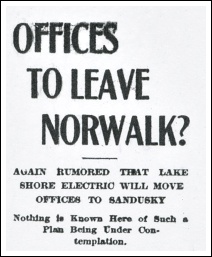

offices were denied in 1908, but the move did occur the next year. (Norwalk Reflector) |

|

1909. The building previously housed the Norwalk Savings Bank. (Drew Penfield) |

|

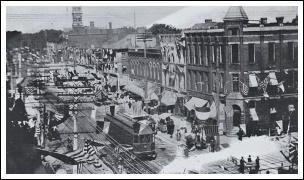

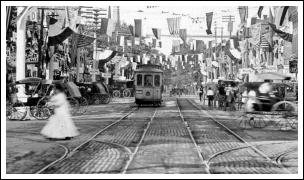

the Firelands centennial in 1909. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

commemorative book. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

limited in the boom years. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

courthouse in 1909. The automobile in the foreground was still something of a rarity. (Dennis Lamont) |

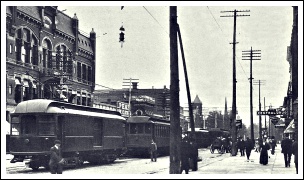

in 1911. Such scenes were typical during the second interurban boom. (Dennis Lamont) |

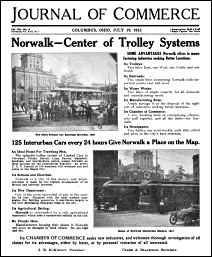

heralded by Norwalk's Chamber of Commerce in this 1913 ad. (Drew Penfield) |

wagon, an automobile, and a crowd surveying the fire damaged courthouse. (Dennis Lamont) |

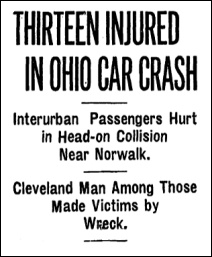

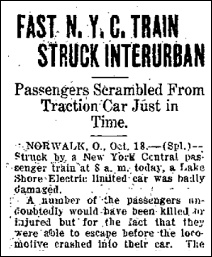

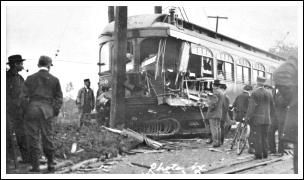

accidents that occurred during the years of very high traffic volume. (Plain Dealer) |

hit by a steam train when it became stranded on the East Main Street crossing. (Sandusky Register) |

York Central train at the East Main Street crossing. (Dennis Lamont) |

York Central train at the East Main Street crossing. (Dennis Lamont) |

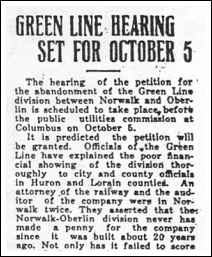

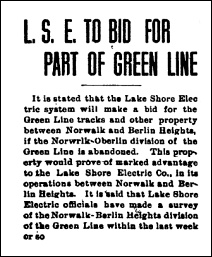

made money and was finally abandoned in November 1923. (Norwalk Reflector) |

tracks to improve service, but ultimately passed on the idea. (Erie County Reporter) |

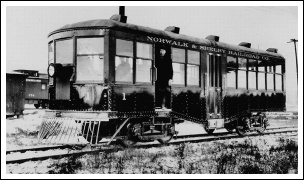

lived Norwalk & Shelby Railroad between 1922 and 1924. (Dennis Lamont) |

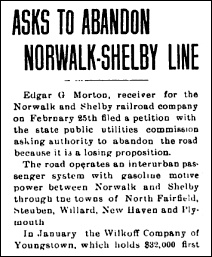

and went out of business after less than two years of operation. (Erie County Reporter) |

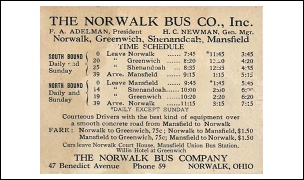

Norwalk and Mansfield after the failure of the railways. (Drew Penfield) |

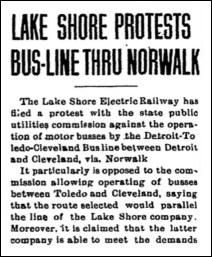

Bus Company to compete for the Norwalk-Sandusky route. (Plain Dealer) |

boom of the multi-car limiteds, went into receivership in 1925. (Dennis Lamont) |

from multiple bus lines throughout the 1920's and 30's. (Erie County Reporter) |

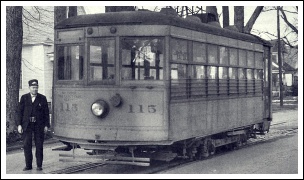

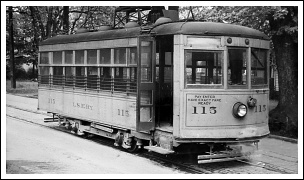

Here he poses with his Birney at the Allings Junction switch where the main line left East Main Street. (W.L. Hay photo) |

the obsolete LSE 101 in December 1925. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

|

|