|

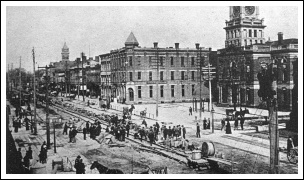

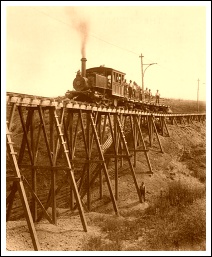

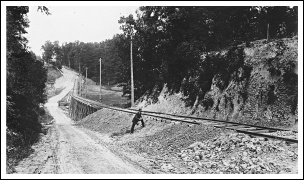

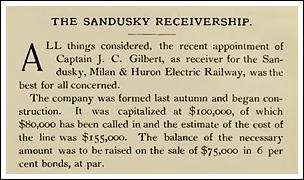

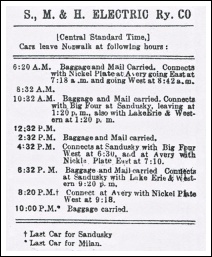

The Firelands In July 1779, at the height of the Revolutionary War, British loyalists burned the people of southwestern Connecticut from their homes. After the war the state of Connecticut offered these people land on the frontier of Connecticut's Western Reserve, in present-day Ohio. The area was called "The Fire Sufferer's Land," and later simply "The Firelands." Many towns in the Firelands were named for the Connecticut towns from which the early pioneers came. Various factors, including the war of 1812, delayed any significant settlement of The Firelands for several years, the first permanent home in Norwalk being that of Platt Benedict in 1817. In 1818, the seat of Huron County was moved from Avery to Norwalk. The village founders encouraged the immigration of skilled craftsmen from New England, and aside from farming, the earliest enterprises were carpentry, cabinetmaking, and blacksmithing. By 1830 Norwalk was home to 310. Many stately New England style homes were built and maple trees were planted along Main Street, which earned Norwalk the nickname "The Maple City." Stagecoach service between Cleveland and Perrysburg was inaugurated in 1827 (extended to Detroit in 1830), following a route through Elyria, Berlinville, Milan, and Norwalk. Milan, four miles north of Norwalk, became a major shipbuilding center and grain port with the opening of the Milan Canal in 1839. Plank roads linked the two towns and greatly benefitted business at Norwalk. Railroads Milan had opposed the railroads in favor of their canal, a move that resulted in the eventual withering of the grain port. Norwalk, by contrast, welcomed the railroads, which had a profound effect on the character of the city, transforming it from a village of farmers and craftsmen into a budding manufacturing center. The Cleveland & Toledo Railroad, opened in 1853, built a locomotive facility at Norwalk, and became the town's largest employer. The Cleveland & Toledo was merged into the larger Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad in 1869. The original narrow gauge Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad began construction at Norwalk in 1877, but went bankrupt in 1879. With investment from Jay Gould in 1881, the railroad was rebuilt to standard gauge and extended to Massillon and Toledo, after which it began to thrive. At the same time Norwalk competed to attract a third railroad, and although the town lost out to Bellevue, the editor of the Norwalk Reflector gave the railroad its popular name: The Nickel Plate Road. Manufacturing quickly expanded to include a foundry, sewing machine factory, umbrella factory, and producers of various wood products. The A.B. Chase Company opened in 1875, and gained an international reputation for its organs and pianos. Lawrence Fisher opened the Fisher Carriage Company in 1880. Two of his sons later moved to Detroit and founded the Fisher Body Company, which became the coachbuilding division of General Motors. Norwalk moved into the modern age quickly: streets and homes were first lit by gas lights in 1859, arc lights in 1886, and electric lights in 1890. A municipal water works provided running water in 1871, and the first stone street paving began in 1877. In 1881 the population exceeded five thousand, allowing Norwalk to incorporate as a city. Being the seat of Huron County, the courthouse was also located at Norwalk. The original wood courthouse was replaced by a brick structure in 1837, which was itself replaced by a larger stone and brick building in 1882. It was gutted by a fire in 1912, but was rebuilt in 1913 and still stands today. By the 1880's, railroads had superseded both the Milan Canal and the stagecoaches. An omnibus operating between Norwalk, Milan, and Sandusky was a last vestige of stagecoach service for many years, but this too would be replaced by a railroad of another kind. First Interurban An electric railway in Norwalk was proposed as early as March 1891, when entrepreneur and politician Tom L. Johnson suggested building a railway from Norwalk to North Fairfield, Milan, Berlin Heights, and Ruggles Grove. The following year two men from Toledo promoted a street railway at Norwalk with branches to North Fairfield, Milan, and Monroeville. A franchise was granted which required construction to begin by July 23, but as far as is known no work ever took place. On July 21, 1892, officials of the recently completed People's Electric Street Railway of Sandusky (known as the White Line) chartered a new company to connect their streetcar line to Huron and Milan. Named the Sandusky, Milan & Huron Electric Railway, it represented a new development known as interurbans. In fact, the SM&H was one of the earliest interurbans in the United States, and for a time was the longest. The merchants of Huron, however, were fearful that the railway would carry their customers away to Sandusky, and put up considerable opposition. The promoters then looked south to Norwalk, with its prospering businesses and a growing population of nine thousand. Thomas Wood, secretary of the SM&H, visited Norwalk on November 15, 1892, and asked the citizens to buy $15,000 worth of stock to fund construction. In contrast to Huron, Norwalk residents embraced the railway and subscribed to $14,000 of stock within a week. The list of stockholders is a who's-who of Norwalk at the time, and includes the mayor, councilmen, bankers, retail merchants, and many others. Norwalk's leading newspaper, The Reflector, also endorsed the enterprise. On December 2, the SM&H directors voted unanimously to extend the railway to Norwalk. A franchise proposal was sent to the city council on December 5, and after several changes were hammered out, was passed 10-0 on December 12. The exact route between Milan and Norwalk remained undecided for some time, and caused no small amount of controversy. The route as originally proposed was to follow present-day State Route 601 south from Milan to the hamlet of East Norwalk, then East Main Street to downtown Norwalk. The vast majority of Norwalk shareholders preferred this. The alternate route, along Old State Road to East Main, was slightly shorter, but passed through a more sparsely populated area and required trestles over Rattlesnake Creek and Perrin's Gulch. Nobody expected the railway to choose such an unfavorable route. But two wealthy investors, one of whom was an SM&H director, lived on Old State Road and strongly influenced the company in the decision. Furthermore, the farm of Capt. John Randolph on that road contained a large gravel bank that the railway sought to obtain for use in construction. A favorable deal for the gravel was more likely if the chosen route was of benefit to Capt. Randolph. The decision was possibly made as early as January 1893, but was apparently kept quiet by railway officials to avoid arousing opposition from the other stockholders. A deal with Capt. Randolph was struck on April 3, and the choice of route was finally announced publicly. Construction of track on East Main began April 11, and on April 25 Norwalk council amended the city franchise to include Old State Road. Although construction began at several places along the line, tying them all together took some time. By May 1893, all track was laid between Sandusky and the hill north of Milan. Stockholders were given opportunities to view the completed work on at least three excursions using the company's tiny construction locomotive and White Line trailer cars. By June 13, the river at Milan was crossed, all grading between Milan and Norwalk was done, and roughly two-thirds of the track was down, but the powerhouse at Milan was no more than a foundation and none of the new interurban cars had been delivered. Service was originally expected to begin July 1, 1893, but the financial panic of that year caused a severe constriction of the capital needed to pay for the powerhouse dynamos, interurban cars, and construction debts. Without adequate cars or power, operations were restricted to a single White Line car running between Sandusky and Milan. July fourth excursions were again run with the construction locomotive, which broke down after only three trips. Still, work was pushed forward, and by the beginning of August nearly everything was in place. From Milan the route followed the east side of Old State Road until it reached the Norwalk city limits, where the track moved to the center of the road. It then turned onto East Main Street and into the center of downtown. A wye was built at the intersection of Main Street and Whittlesey to turn the cars. One final obstacle hindered the progress of the first car to Norwalk. The story has been confused and embellished over generations of retellings, but the actual events were clearly reported by The Norwalk Reflector at the time. The Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad, apparently attempting to relieve itself of some expenses, obtained an injunction on August 4 to prevent the SM&H from laying track on the bridge carrying East Main Street over the railroad. The reason given was that the track would present a danger to life and property, but in a meeting the next day, the Wheeling's attorney requested the SM&H to agree to pay half of all bridge maintenance, in perpetuity. Thomas Wood refused, but did agree to pay for any damages caused by the SM&H track, which appeared to resolve the impasse. Four days later, on the morning of August 9, Thomas Wood, A.W. Prout, and W.H. Gilcher took People's Electric Railway car number 4, a single-truck streetcar from Sandusky's Water Street route, over the line to Norwalk. Upon reaching the East Main bridge, however, they discovered that the track was not in place, and were informed that the Wheeling had not lifted the injunction. Incensed, the officials immediately called on Norwalk city council, which convened a special session and passed a resolution ordering the track to be laid. An hour later the track was in place and the little streetcar rolled across the bridge to the cheers of a crowd which had gathered to witness the action. The crowd was then invited to take a free ride to downtown, and quickly filled the car to capacity. Upon entering downtown Norwalk, the car was greeting by a throng of townspeople and children. The occasion was immortalized in a photograph, showing the streetcar in front of the Huron County courthouse. In the background the five-story Glass Block, home of the Hoyt & Jackson Company department store (another sign of Norwalk's ascendancy) is under construction. This first car did not inaugurate regular service, however, as the company was in dire need of funds. A considerable number of subscribers had not paid for their stock, and due to the financial panic of that year the company was unable to sell its bonds. Thirty thousand dollars was needed to pay for equipment and the looming construction debts, including a lien on the Milan powerhouse, which was not yet operational. Payment was required for the dynamos, which had been delivered but held on a railroad siding, as well as the interurban cars, which had not been delivered. On August 19, the directors and shareholders agreed to put the company in receivership so the debts could be paid and the railway protected from creditors attempting to seize assets. President J.C. Gilchrist resigned in order to be named receiver. Five days later, Gilchrist arranged a payment plan with the Akron Car Co. and Pullman Palace Car Co. for the cars, and Westinghouse for the motors, dynamos, and other electrical equipment. The work of installing the dynamos and wiring the powerhouse began immediately, and five of the railway's handsome new cars, painted snow-white with gold lettering, were delivered from Akron over the following week. One of these, delivered on August 30, was the Norwalk city car. Officially numbered 15, its sides were emblazoned with "East & West Main Street Line." It was sixteen feet long, rode on a single four-wheel truck, and was powered by a single 30 horsepower motor. The first of the new cars (possibly the city car) was run to Norwalk on September 1, 1893 with current from the Milan powerhouse. Regular service began two or three days after. The one-way fare between Sandusky and Norwalk was thirty five cents, fifty cents for the thirty two mile round trip, and five cents for the Norwalk city car. The ticket office and waiting room opened at 14 Whittlesey Ave. in October. That same month the remaining bonds were finally sold and the company began paying off its debts. On December 23, 1893, the Sandusky, Milan & Huron emerged from receivership, and on January 30, 1894 was officially renamed the Sandusky, Milan & Norwalk Electric Railway. Although some hope remained of building a branch to Huron, the change was an acknowledgement by the directors that Norwalk had been instrumental in the realization of the railway. The decision to change the name had been made months earlier while the first cars were still under construction. As a result they were delivered with "SM&H" lettering on the ends and "Sandusky, Milan & Norwalk" spelled out on the sides. Business ramped up quickly in the first half of 1894. At the start of the year, the railway had seven cars on hand (three closed cars, three open "summer" cars, and the Norwalk city car) and work was under way to fully prepare them all for the expected rush of patrons in the spring. U.S. Mail service began October 9, 1893, and on March 6, 1894 the railway signed a five-year contract with the American Express Co. to carry packages on the cars. Combine number 9 was used for express initially, but sometime around 1896, car 7, originally an open car rebuilt as a closed coach, was converted yet again into an additional combine. An average of five hundred pounds of mail was hauled daily, while freight and express increased modestly each year. Although no great amount of freight was ever carried, the company did build a small freight car in the shop at Milan, which made its debut on April 4, 1894. An obviously home-built affair, it was little more than a boxcar body mounted on single-truck running gear salvaged from an old Sandusky streetcar. It was certainly the ugly duckling of the SM&N roster, and there is no record of it ever having a number. It was used for freight, maintenance, and whatever else was required. The railway also installed its own telephone and telegraph service along the right-of-way, which was put into service May 1, 1894. West Main Street Long before cars began running, even before work in Norwalk began, the SM&H was looking to expand down West Main Street to the west city limits. Whether the idea originated with the railway or the people of Norwalk is not clear, but a petition for the consent of the landowners on West Main was circulated in January 1893. The Reflector editorialized strongly in favor, imploring West Main residents to "sign it promptly and cheerfully. Do not stand in the way...but work continually for the advancement of the city and for the public good." Not everyone felt streetcars on West Main were good for the city, however. An opposing petition was also circulated out of fear that the railway would spoil what was considered the city's most beautiful street. Both petitions were presented to the city council on February 28, 1893, along with a letter from the SM&H asking for a franchise on West Main. A franchise was granted and predictions were made that work would begin as soon as spring weather allowed. In fact, construction on West Main was largely ignored throughout 1893, while the rest of the railway was built, and well into 1894. Another Wheeling & Lake Erie bridge was one likely reason for the delay. The old wooden bridge over the W&LE tracks was described as "dangerous" and "ramshackle," and was slated to be replaced with an iron bridge on stone abutments. The SM&H was probably content to wait until the new bridge was built, especially given the financial difficulties of 1893. Poles were delivered and set in May 1894, and statements regarding imminent construction were made several times throughout the year. As the September deadline approached, however, not a single foot of rail had been laid. Meanwhile, SM&N management was thinking even further ahead. On September 6, 1894, word was given that the railway planned to build another 3½ miles west to Monroeville. The company requested an additional sixty days to complete West Main, optimistically estimating they could have the entire extension to Monroeville complete in that time. Sentiment in both Norwalk and Monroeville was favorable, and the council moved the deadline to November 16, 1894. Whether the Monroeville plan was sincerely the reason more time was requested is somewhat questionable. Although the directors voted on September 14 in favor of building to Monroeville, they did not believe the work could be done before spring. Furthermore, on October 8, Thomas Wood told The Reflector that an order for the Johnson Co. girder rails necessary to complete West Main could not be filled in less than eight weeks. The railway suggested using T-rail instead, but council refused. In any case, the girder rails were obtained and track was laid the entire length of West Main by November 2. Local cars began running the next day, but only as far as West Street, due to a shortage of trolley wire. Operations the full length of East and West Main streets began November 24. Car 15 made a trip every half hour between 6:30 AM and 11:00 PM. The fare from one end of town to the other was five cents. West end residents were very satisfied with the service, and immediately urged the company to put on a second city car. It was another four years before the second car, a single-truck Pullman carrying number 17, arrived. The Monroeville extension never materialized, almost certainly for financial reasons. Beside the cost of grading, track, and bridgework, the railway's direct current power supply would have been insufficient to run interurban cars up the hills of the Huron River valley at such a distance. The only options would have been to convert the powerhouse to alternating current and build substations, build a new powerhouse, or purchase electricity from the commercial power plant at Norwalk, none of which were financially practical. Management appears to have preferred selling rather than investing in further expansion. Between 1895 and 1899, various out-of-town capitalists negotiated for the purchase of both the SM&N and the People's Electric Railway. In October 1899, New Yorker S.M. Bullock, representing Charles D. Barney & Company of Philadelphia, purchased both railways for $140,000. Soon after, they were reorganized into a single company named the Sandusky, Norwalk & Southern. In early 1901 the company bought out the remaining stockholders and entered a partnership with the Everett-Moore syndicate. Everett-Moore already had strong ties with the SM&N. During the 1893 receivership, Gilchrist had installed his young office assistant, Fredrick Coen, as the railway's secretary. In 1895, Coen took a position with Everett-Moore's new Lorain & Cleveland Railway. Everett-Moore also incorporated the Sandusky & Interurban railway in 1898, managed by Thomas Wood. In September 1901, all three of these properties were merged into the Lake Shore Electric Railway, along with one final link in the chain. |

including the Firelands in present Huron and Erie counties. (Ohio Historical Society) |

Norwalk, probably during the 1880's when it was the town's largest employer. (Henry Timman) |

|

over the first four miles of track laid north from Norwalk. (C.H. Kellogg) |

|

Norwalk's many craftsman manufacturing industries. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

1880. Two of Fisher's sons would later establish the Fisher Body division of General Motors in Detroit. (Ohio Historical Society) |

|

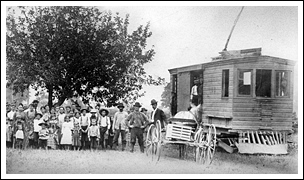

reduced the stages to omnibus service between nearby towns which was later replaced by electric interurbans. (Milan Historical Society) |

|

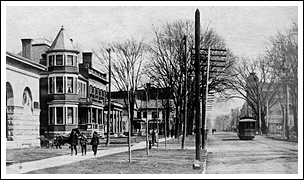

railway came to Norwalk. At left is the F.B. Case Tobacco Company and Hester Ave. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

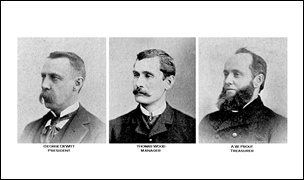

Andrew Prout, treasurer, helped bring the Sandusky, Milan & Huron Electric Railway to Norwalk in 1893. (Street Railway Review) |

|

on November 15, 1892, which rallied the city in favor of the railway. (Norwalk Reflector) |

|

council granted a franchise to the SM&H on December 12, 1892. (Erie County Reporter) |

|

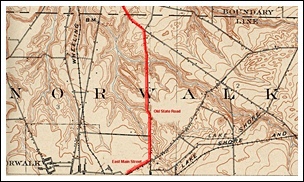

and East Main Street between Milan and Norwalk. (Drew Penfield) |

|

and East Main Street. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

primarily for construction, on the trestle at Perrin's Gulch. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

Creek between Milan and Norwalk. Old State Road is alongside. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

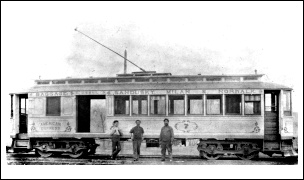

number 4, posed in front of the county courthouse and surrounded by excited townspeople on August 9, 1893. (C.S. Bateman photo) |

|

receivership in October 1893. (Street Railway Review) |

|

1893 ad for the Jewett Car Company. (Dennis Lamont) |

work providing local service on Main Street. (John A. Rehor) |

depicting one of the railway's short-lived double-deck cars. (Willis McCaleb) |

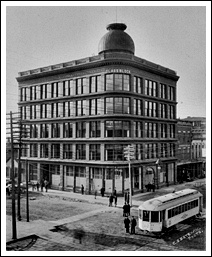

the Glass Block, Norwalk's tallest building. (Drew Penfield) |

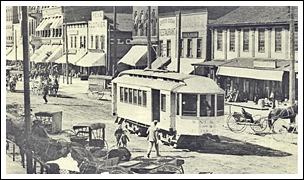

passes horses and carriages on East Main Street in 1895. (C.S. Bateman photo) |

converted to a combine for express service. (Dennis Lamont) |

The utilitarian car was also used for maintenance work. (Dennis Lamont) |

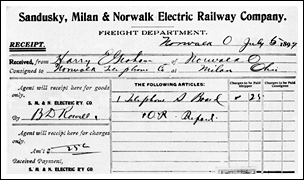

Norwalk to Milan on the SM&N in July 1899. (Dennis Lamont) |

in February 1894. (Norwalk Reflector) |

car at the corner of Main and Whittlesey around 1893-94. (Dennis Lamont) |

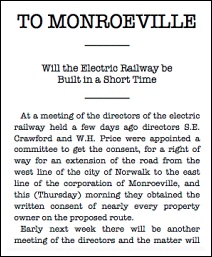

consent for an extension to Monroeville. (Norwalk Reflector) |

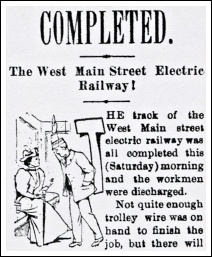

on November 3, 1894. (Norwalk Reflector) |

The Glass Block can be seen in the background. (Dennis Lamont) |

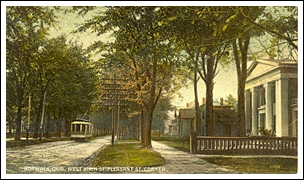

(Drew Penfield) |

Norwalk city service. This is the builder's photo. (George Krambles) |

(Dennis Lamont) |

the late 1890's for capitalists interested in buying the SM&N. (Cleveland Plain Dealer) |

investment firm that took ownership soon partnered with the Everett-Moore syndicate to form the LSE. (Cleveland Plain Dealer) |

|

|

|