|

Steel Comes to Lorain

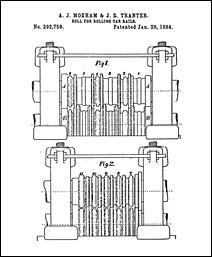

The Johnson Steel Street Rail Company was founded in 1883 by Tom Loftin Johnson and Arthur James Moxham. Starting at age 14, Johnson worked his way up the ranks of a small Louisville, Kentucky streetcar line owned by brothers Alfred and Bidermann du Pont. In 1873 he patented an ingenious coin-operated fare-box for streetcars, and in 1883 developed a new type of streetcar girder rail that was stronger and more durable than the contemporary iron strap and stringer rails. A.J. Moxham was a relative of the Louisville du Ponts and a longtime friend of Tom Johnson. His experience in the rolling mills of Louisville and Birmingham had earned him the title of ironmaster and a patent for the process of rolling the Jaybird rail invented by Johnson. The Johnson Company was established in Johnstown, Pennsylvania with Moxham as president and Johnson himself as vice president. Among many other interests, Johnson became deeply involved in politics, and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1891. When the Panic of 1893 began to affect Johnson Company profits, Moxham and his staff proposed two major changes to stay competitive. Until that time the company was primarily a rolling mill using steel produced by another mill. The decision was made to expand operations into a fully integrated steel mill that would produce its own raw steel, rails, and other finished steel products. This new mill would be built in a location closer to raw materials, markets for the finished products, and transportation networks. Sites near Youngstown, Fairport, and Cleveland were all considered. It was the little village of Lorain, however, that provided all the elements Johnson and Moxham were looking for: a river and harbor on Lake Erie, railroads, and best of all, plentiful cheap land. Early in 1894, Johnson associate J.B. Coffinberry quietly began acquiring options on land south of the Black River in Sheffield Township, an old shipbuilding site known as Globeville. The area was primarily forest, dotted with small farms and crossed by the primitive Globeville Road, the main route between Lorain and Elyria. Coffinberry kept the company's intentions secret to avoid a surge of speculation that would drive up land values. One account says that the Hyer farm was purchased under the pretense of opening picnic grounds. On April 2, 1894, the Johnson Company formally announced its intentions in a letter to the village council. The company would purchase the land and build their new mill near Lorain if the village would agree to widen and dredge the river and annex the land into Lorain. The council quickly agreed and the Johnson Company purchased 3700 acres of land under a subsidiary, the Sheffield Land and Improvement Company. The mill and other industrial buildings would occupy about 1200 acres. The remainder was intended for development of a model residential community for the workers, complete with wide paved roads, sidewalks, sewers, schools, parks, and all the modern conveniences. It would become known as South Lorain. The Last Horse Car Tom Johnson was an experienced and skilled street railway manager, having owned railways in Indianapolis and Cleveland. He shrewdly purchased small, faltering street railways that his experience told him had potential, applied his management skills, made physical improvements, then reaped the profits. The tiny, bankrupt, horse-drawn railway in Lorain was a perfect opportunity in more ways than one. Not only was it an inexpensive property that could be greatly improved for profit, it could also transport the army of workers who would build and operate the new steel mill. The railway was purchased and reorganized with Tom Johnson, A.J. Moxham, Max Suppes, W.T. Bien, and Frank Vernam as shareholders. Bien was made president, while former receiver Frank Norcross was retained as superintendent. On June 11, 1894, the village council passed ordinance 262 granting a franchise to the new company to build and operate an electric railway and extend its right-of-way east on Dexter Street (present East 21st Street) and the Globeville Road to the steel mill property. After passing through South Lorain the railway would turn south and continue to Elyria. Workers from Elyria would then have a reliable and direct mode of transportation to the mill. When it became known that the horse cars were to be replaced, the Evening Herald newspaper approached Superintendent Norcross about making the last run a celebration of progress from horse cars to electric and steel. On July 14, 1894, President Bien announced that the last horse car would run that evening, and Norcross quickly made arrangements for an event. The railway's two open cars were decorated with flags and bunting and each was drawn by a team of horses. At 9:00 PM the cars were taken to the intersection of Erie and Broadway where an estimated one thousand people gathered to witness the occasion. The Herald, which also printed pink souvenir tickets, gave a lengthy report, which read in part: The Lorain Cornet Band was in the first car with Charles Krautter as driver and in the second car Major Breckenridge held the ribbons. At just 9:35 Conductor Norcross gave the word to start and the cars moved off amid the cheers of the spectators and music by the band. All along Broadway a crowd had gathered to cheer the train. Each man on board had a ticket and it was duly punched and handed back.The Herald article listed the names of more than forty people who rode the last cars, many of them prominent citizens, such as doctors, clergy, former mayors, and respected local businessmen. With the horse cars out of service, the original carbarn on Penfield Ave. was abandoned and remained vacant for some time. By 1900 it was being used as a livery stable, but by 1905 it had been torn down. A year after the last run of the horse cars, original founder Walter Root was involved in another venture, The East Lorain Street Railway. Chartered on June 5, 1895, this 2½ mile electric line operated on East Erie Ave. between the Black River and the Root farm at Root Road. Despite reports of a plan to eventually reach Cleveland, it was most likely established to secure a franchise expected to become very valuable in the near future. In January 1896, Street Railway Journal reported that Johnson's railway had received permission to extend its line across the Black River bridge. This may have been part of a plan to purchase the tiny east Lorain railway, but any such plans were soon rendered moot when the Lorain & Cleveland Electric Railway purchased the property to obtain the franchise. Building The Electric Line Converting the Lorain Street Railway to electric cars necessitated a complete rebuilding of the line, and work began almost immediately after the horse cars ceased. The existing iron strap and stringer track on the dirt road was torn up, a stable new roadbed prepared, and new Johnson girder rail laid. With enormous resources and labor available, the Johnson Company wasted no time rebuilding and extending the railway so that it could be used to move men and materials for construction of the mill. To expedite construction, single track was laid over most of the line (the major exceptions being a couple lengths of double track on Fulton and 10th Ave.), although the right to lay double track "when the company desire so to do" was granted in the franchise. In order for the cars to reach downtown Elyria a new bridge was required on Lodi Street. The small iron and wood wagon bridge over the west branch of the Black River was nowhere near capable of handling even the smallest electric cars. In June 1894 the city took bids for a substantial new bridge made of sandstone block. Not only did this bridge safely carry interurban cars above the river's west falls for the next forty-four years, but it still carries four lanes of modern automobile traffic today. At South Lorain, work began on the powerhouse and the railway's new carbarn. The first powerhouse was a simple wood frame structure, most likely intended to be temporary until the larger, permanent powerhouse at the mill was operational. It was nearly complete by August 1894 and served a dual purpose: providing power to both the railway and the overhead arc lighting, which allowed construction of the mill to continue around the clock. The carbarn was a much more substantial brick structure, and thus took longer to complete, being finished in September. It was 227 feet long, 36 feet wide, and housed a double row of track with inspection pits and repair facilities. About halfway between South Lorain and Elyria, at what is locally known as the North Ridge, was a small sandstone quarry. It had existed for many years, operated by the Esctruth family, and provided foundation stone for many early homes in the area. The Johnson Company purchased the quarry and built a siding from the railway. Sandstone was hauled over the railway to the mill site where it was used in both the mill structures and the residences and businesses of the new South Lorain neighborhood. A rock crusher was also installed at the quarry to make stone ballast for the railway tracks. Opening day of the new Lorain Street Railway came on September 15, 1894. One of the horse-drawn railway cars posed for a photograph head-to- head with a new electric car. As was customary, the first run carried company officials and local dignitaries. Legend has it that the car made a special stop at Dexter Street and North Fulton, where local character Catherine "Auntie" Furgeson, an elderly former slave, lived in a small cabin on the old Globeville Road. In May 1894 she was befriended by Tom Johnson, who gave his word that she could remain in her beloved cabin near the river for the rest of her days, despite his purchase of the land for the steel mill. The officials and their families riding that first car in Septmeber were invited to her humble home, where they enjoyed a substantial lunch before continuing their journey. Soon the electric cars were running between Lorain and Elyria on a fifteen minute headway. At a time when most street railways operated at speeds around 15 miles per hour, the Lorain Street Railway ran at an impressive 25 to 30 miles per hour. Fares were five cents within the city limits of Lorain and Elyria, or ten cents for a full trip between the two cities. Children under the age of five rode free when accompanied by a paying adult. The railway's early cars were all from the Stephenson Company, and at least the passenger cars were all single-truck. How many cars the railway had at opening is unknown. An order for additional cars was placed with the Stephenson Company in late 1894, but again the number is unknown. Within a few years the roster totalled seventeen motor cars. Trailers were added to the motor cars during rush hours when large numbers of mill workers rode to and from their jobs. An open trailer coupled to one of the Stephenson motor cars can be seen inside the carbarn in an 1894 photo (below). Confirmation is lacking, but it's likely that these early trailers were the former horse-drawn streetcars of the original Lorain Street Railway. In the days before destination rollsigns, most railways painted the names of their routes on the sides of their cars. The Lorain Street Railway cars were emblazoned with the names of Lorain and Elyria and a logo of two clasped hands, representing the joining of the cities. This gave rise to the common misconception that the railway was named the Lorain & Elyria Electric Railway, although it was sometimes informally referred to as such. Most commonly it was called the Yellow Line because of the cars' bright yellow paint scheme. The competing Cleveland, Elyria & Western, which later became the Cleveland Southwestern, was known as the Green Line. The railway also owned a small single-truck package car for express freight, and as set forth in the franchise, charged ten cents "for each package, parcel or piece of baggage weighing a hundred pounds or fraction thereof." No documentation of the railway's express service is known to exist, but several inferences can be made. The U.S. Express Company had an office at 42 West Erie, just off the Broadway intersection. (The National Express Company briefly operated an office next door.) The freight car would stop here and packages would be carried between the office and the waiting car. U.S. Express had another office at 576 Tenth Ave. in South Lorain. The Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad's freight depot was located at the Elyria end of the railway, but express was handled at the U.S. Express office near the passenger depot, a short distance away. Packages were most likely transferred between this office and the electric cars by way of horse-drawn wagons. On February 21, 1895, the city of Lorain officially annexed nearly one third of Sheffield Township, including the new mill and the South Lorain neighborhood. On April 1, 1895, the first blow of steel was produced in the new mill. Over one thousand men had labored to clear the land, build the mill, and move operations from Johnstown, Pennsylvania to Lorain. The undertaking was massive, and all the more amazing in light of the timeframe in which it was completed. In only twelve months the farms, forest, and primitive road of Globeville had been transformed into the steel mill, workers' neighborhood, and electric railway of South Lorain. The Route Upon opening in 1894, the railways total length of track (including the short double tracked sections and passing sidings) was 11½ miles, stretching from the center of Lorain's business district to within three hundred feet of Elyria's town square. At the intersection of Erie Ave. and Broadway in Lorain, the old turntable used by the horse cars was replaced with a loop. Double track extended a few blocks south of the loop on Broadway and from there single track followed the same route as the old horse line on Broadway and Penfield Ave. The new extension followed Dexter (21st Street) east across Elyria Ave. and the Cleveland, Lorain & Wheeling Railroad tracks to the old Globeville Road, which had been severed by the steel plant. A new road, North Fulton, ran southeast and connected Dexter with 10th Ave. (present East 28th Street.) Continuing east on 10th Ave. the railway passed the offices of the Johnson Steel Company, the railway carbarns, and the mill itself. At that time 10th Ave. ended at present Grove Ave. and the railway turned south onto a private right-of-way which extended to Elyria. Upon reaching Elyria, the tracks followed Lodi Street (present Lake Ave.) and terminated in a loop at the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad. |

entrepreneur, and politician. (cable-car-guy.com) |

(Johnson Company Archives) |

|

"Jaybird" streetcar rail. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

|

|

complex Jaybird rail, from rough shape (1) to the finished profile (11). (Dennis Lamont) |

|

(Dennis Lamont) |

|

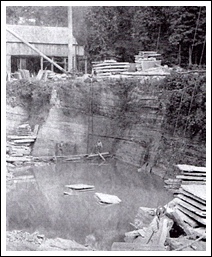

Ravine would be dammed to make a reservoir for the steel mill. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

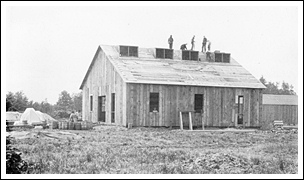

1894. The building is a temporary construction office. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

Railway's horse-cars on July 14, 1894. (Dan Brady) |

|

the "new" 1894 electric car. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

railway in July 1894. View is south on Broadway. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

(Dennis Lamont) |

|

powerhouse near completion in July 1894. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

powerhouse, July 1894. Same engine would be re-used in later powerhouses. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

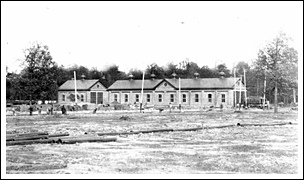

just begun. (Dennis Lamont) |

are taking shape. (Dennis Lamont) |

pipes for residential water/sewer service. (Dennis Lamont) |

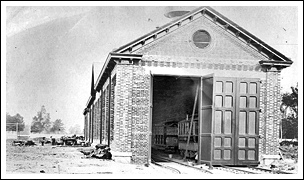

the start of service. (Dennis Lamont) |

leads into the steel plant property. (Dennis Lamont) |

(Dennis Lamont) |

the south. (Dennis Lamont) |

throughout the mill and South Lorain. (Sheffield Village Historical Society) |

day, September 15, 1894. (Dennis Lamont) |

(Dennis Lamont) |

(Drew Penfield) |

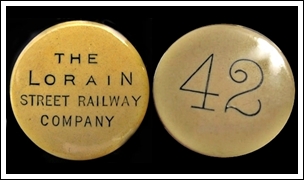

when collecting their pay or riding the cars. (Drew Penfield) |

and 14th Ave. (now E. 32nd) in South Lorain. (Dennis Lamont) |

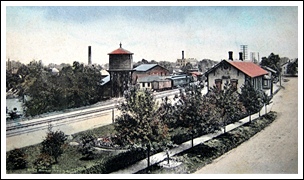

Moxham house, as seen in this view of 11th Ave. ca1900. (Jim Wallace via Flickr.com) |

Broadway and Penfield Ave. (Drew Penfield) |

Streets to 10th Ave in South Lorain. (Drew Penfield) |

loop. Express office was just off photo at right. Streets were still unpaved and muddy in 1895. (Dennis Lamont) |

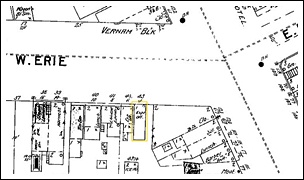

West Erie just off the Broadway loop. (Drew Penfield) |

L.S.Ry tracks at left, B&O railroad crossing in background. (Dennis Lamont) |

Works in 2012. (Dan Brady photo) |

in 1903. (Dan Brady) |

steam engine at the steel plant's North Fulton Ave. gate. (Dennis Lamont) |

company offices are under construction at left. (Dennis Lamont) |

in the early 1900's. (Donald J. Emerick) |

(Dennis Lamont) |

(Dennis Lamont) |

and Elyria on private right-of-way. (Drew Penfield) |

Lake Ave.) to a loop at the LS&MS railroad tracks. (Drew Penfield) |

The old iron and wood bridge is in the background. (Dennis Lamont) |

Street bridge above the West Falls of the Black River. (Drew Penfield) |

the Red Mill, which was above the Black River's east falls. (Elyria Public Library) |

LS&MS depot at Depot Street and East Ave. (arrow). (Drew Penfield) |

|

|

|