|

Lorain History Lorain was originally established as a frontier outpost at the mouth of the Black River around 1807. In the 1830's it blossomed into the thriving lake port of Charleston when local merchant and civic leader Russell Penfield organized a plank toll road connecting Charleston with the county seat in Elyria. In 1850, however, the Cleveland & Toledo Railroad bypassed Charleston and went to Elyria instead. Products which had previously come north on the plank road to be shipped on Lake Erie began shipping by rail from Elyria. Charleston lapsed into a state of depression almost overnight. For more than twenty years the small town's population and busines was sustained only by fishing and small scale shipbuilding. In 1872 an unexpected period of growth and renewal began, now known as Lorain's "Great Awakening." That year the Cleveland & Tuscarawas Valley Railroad built a branch north to the mouth of the Black River, where it established coal and ore docks and a large car and locomotive facility. (Later renamed the Cleveland, Lorain & Wheeling, it would be absorbed by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in 1909.) Commerce returned immediately, and the town's reputation flowered once again. In 1874 the town was officially incorporated as the Village of Lorain. In 1881 the Nickel Plate Railroad came to Lorain, and later that same year the town's first major factory was opened. Hayden Brass Works Joel Hayden came to Lorain from Massachusetts, where his family had owned various mills and foundries. In January 1881, Hayden and railroad magnate Amasa Stone organized the Joel Hayden Brass Works to manufacture brass fittings and plumbing supplies. An eleven acre site between present Broadway, Elyria Ave., 18th and 21st Streets was chosen for its proximity to the railroads and the river. Several large brick buildings housed the foundry, mill, and machine shops. By 1883, the company was Lorain's largest employer. Both the company and local businessmen purchased tracts of land near the factory and encouraged employees to buy lots and build homes, thus creating the neighborhood of Central Lorain. The Hayden Brass Works soon became part of the United Brass Company, and in 1886 was reorganized again as the Lorain Manufacturing Company. Despite these developments, Lorain was still a very small, rough, and rustic village. Not a single foot of any road in town was paved. Rain turned the streets to thick, sticky mud; in summer they turned to dust. Most businesses were located on only one side of Broadway, where a plank sidewalk allowed easy foot travel. Most customers would not cross the muddy or dusty road to reach businesses on the other side. An expanse of such road, without sidewalks and lined by open fields, separated the brass works and Central Lorain neighborhood from the business district downtown. While many workers lived in Central Lorain, they had to walk north to do business. Workers who lived at the north end of town walked to the brass works each day. Most residents did not own a horse and only nineteen owned bicycles, which were only of use in good weather. First Street Railway The opportunity for improved transportation in Lorain caught the attention of eight local businessmen, who organized the Lorain Street Railway to connect the town's business district to the factory and neighborhood south of town. The list of the founders is a who's who of Lorain's business community at the time. Thomas R. Bowen was a tailor and proprietor of the Union Clothing Store on Broadway; Frank B. Vernam served as mayor of Lorain from October 1877 to April 1878, and was a real estate broker; Thomas Wilford and Robert Cowley were lake captains of wide renown; Irwin D. Lawler established and edited the first newspapers in both Lorain and Amherst, and was also a real estate broker and attorney; John B. Tunte was the leading grocer in town and a real estate broker in partnership with Lawler; Walter Root was a farmer and member of a pioneering family involved in various business ventures in town, including a feed store and a bank. The final investor is listed as "H.F. Borrow", but was most likely Henry Barrows - proprietor of the Lorain Flouring Mills. Thomas Bowen was elected president of the new company, while Frank Vernam served as manager and superintendent of the railway. At least two other investors became interested in the railway at a later date. One was Frank Norcross, superintendent of the Lorain water works. Another was F. Wayland Brown, who owned a foundry supply company in Cleveland, managed a rubber company, and would later become manager of the Youngstown Street Railway. On May 7, 1888, the village council passed ordinance 138, granting the Lorain Street Railway a twenty-five year franchise to lay track and operate horse-drawn streetcars on Broadway and Penfield Ave. At the time, Broadway extended only to 17th Street where it split into Elyria and Penfield avenues. (In 1907 the Penfield Ave. name was dropped and the entire road became Broadway.) Roughly one and a half miles of single track were laid on the muddy streets from the intersection of Erie and Broadway south to Dexter Street (present-day 21st Street). At each end of the line the cars were rotated on a small turntable. A barn for the cars and horses was located at the north end of Penfield Ave. near present-day 18th Street. The railway owned two open cars for summer, two closed cars for cold weather, and nine horses. The franchise permitted fares of five cents for a one-way trip over the line, or ten cents per trip between the hours of 10:30 P.M. and 6:00 A.M., and required at least five trips each way per day. The horse cars were in operation only about one year before tragedy struck, not on the railway but on the lake. On the morning of September 15, 1889, nine Lorain businessmen and civic leaders boarded a naphtha launch named Leo for an excursion to Cleveland. That evening, a few miles east of Rocky River, the Leo met its end. The exact cause was never determined, but bad weather or a boiler explosion were the most likely explanations. All those aboard were killed, including Irwin Lawler and John Tunte. The tragic loss of these ambitious entrepreneurs was a great blow to Lorain. It is believed that either Lawler or Tunte had been treasurer of the railway, as local jeweler George Clark joined the company and assumed that position shortly after the Leo disaster. In 1892, a newspaper reported on a near tragedy on the railway itself, when a stubborn streetcar horse stopped on the Nickel Plate railroad crossing. A collision with an oncoming train was barely averted. The railway's southern terminus was located at another destination of importance to local history. In 1885 Gilbert Hogan was drilling for natural gas on his property on Penfield Ave. between 20th and 21st Streets. Instead of gas he struck a well of mineral-rich, sulfur-laced water. At the time such water was believed to have medicinal properties and Hogan soon opened the Devonian Springs baths. Across the street he built a large hotel to accommodate his clientele. The water was also bottled and exported. Apparent lack of business caused Hogan to sell the hotel and in 1892 it was purchased by the Sisters of St. Francis and converted to an orphanage and old age home known as St. Joseph's Institute. Doctors began bringing severely ill patients to the institute and it soon evolved into St. Joseph's Hospital. The original hotel building was replaced by a large stone building in 1917, which has been a prominent Lorain landmark ever since. The mineral baths remained open at least until 1896 but were closed by 1900. A Second Depression Despite the best intentions of the line's founders and the opportunity it offered the residents of Lorain, the street railway was never a financial success. The population of the entire village of Lorain was less than 5000 in 1890, and the railway was limited to only the sparse neighborhoods and businesses along its short route. Ridership was never high nor consistent. George Clark would later state that there was not a single week in the railway's seven year existence in which it turned a profit. The Panic of 1893, an economic depression caused by a bubble in railroad speculation and bank failures, bankrupted the already unstable Lorain Manufacturing Company. Employees worked without pay for two months before finally walking out on June 30, 1893. Without the ability to pay its workers or other debts, the factory closed for good. Various buildings in the complex were used by other manufacturers until 1905, when the site was demolished and divided into lots. The National Vapor Stove Company, which had recently moved its operations from Cleveland to Lorain, became the second local victim of the panic when it closed in August. (It would reorganize as the National Stove Company and resume production in 1895.) The loss of these employees as riders, and the sharp decline in business throughout the city at large, forced the perennially unprofitable Lorain Street Railway into bankruptcy. Frank Norcross was named receiver and the little horse-car line struggled on. For the second time, the bright future of Lorain was darkened by economic depression and loss of industry. Unknown to most, however, one man was about to make a decision that would transform Lorain into an industrial giant for decades to come. |

appeared just before the "Great Awakening." (Dennis Lamont) |

River in 1875. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

1881. It was Lorain's largest employer at the time. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

Note the dirt road, plank sidewalk, and hitching posts. (Dan Brady) |

|

two of the railway's original founders. (Drew Penfield) |

|

who died in the sinking of the Leo in 1889. (Black River Historical Society) |

|

became treasurer of the railway in 1889. (Dan Brady) |

|

leaving to manage the Youngstown Street Railway in 1893. (Street Railway Review) |

|

Lorain Street Railway. (Lorain Public Library) |

|

Circles at each end are turntables, star is location of barn. (Drew Penfield) |

|

rail commonly used on horse-drawn railways in the 1880's. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

on Broadway in the 1890's. (Dennis Lamont) |

of small turntable the Lorain Street Railway employed at each end of the line. (www.columbusrailroads.com) |

of 18th Street (then named Forest St.) and the brass works. (Drew Penfield) |

at the barn in the late 1880's. (Dennis Lamont) |

coming St. Joseph Hospital in the 1890's. (Drew Penfield) |

Devonian Springs hotel. (Dan Brady photo) |

and the Clark & Jewett Buildings, as they originally appeared. (Dennis Lamont) |

Inset photo shows face (believed to be Thomas Bowen's) on upper facade. (Dan Brady photo) |

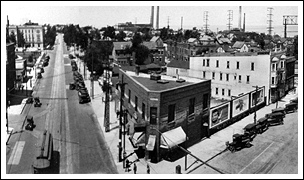

Broadway and Erie, seen here in the late 1920's. (Dennis Lamont) |

store. The T.R. Bowen building stands next door (left). (Google Earth) |

the 1900's. Note the anchors above the doorway. (Loraine Ritchey) |

here in the early 2000's. (Dave Cotton photo) |

|

|

|