|

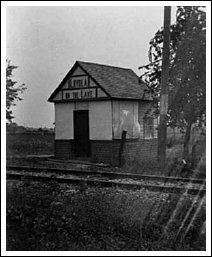

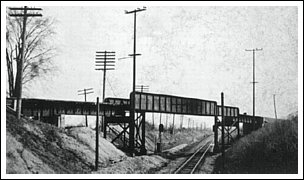

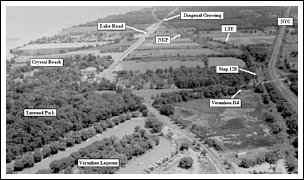

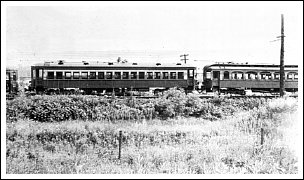

Frederick Coen In 1891 brothers Edward and Frederick Coen moved from Rensselaer, Indiana to Vermilion where they helped organize the Erie County Banking Company. Edward became the bank's first vice president under J.G. Gilchrist, while the younger Frederick held the position of "office assistant." In 1893, at the dawn of the interurban era, the bank invested in the upstart Sandusky, Milan & Huron Electric Railway. The railway was soon reorganized as the Sandusky, Milan & Norwalk and the bank sent young Fred Coen to act as the railway's secretary and keep watch over their investment. Over the next two years Fred's knowledge and skills impressed the men of the Everett-Moore and he was offered the position of secretary with the new Lorain & Cleveland Railway in 1895. In 1907 he was promoted to vice president and general manager of the Lake Shore Electric. In 1927 he became president of the LSE under the Cities Service Company and remained in that position for the duration of the railway's existence. He then continued as head of the Lake Shore Coach Company, the bus line which suceeded the LSE, until 1940. Harwood & Korach wrote: "The life of the Lake Shore Electric and the life of Frederick William Coen were one and the same...More than any single individual, he was responsible for the company's prosperity during its good days and its survival in the bad ones." The First Car In 1901 the Sandusky & Interurban railway was stretching east to connect with the Lorain & Cleveland Railway. By the end of the year the S&I and the L&C had become part of the Lake Shore Electric. Track and bridges had been hastily built between Lorain and Vermilion to complete the connection. According to a contemporary edition of the Vermilion News the very first streetcar to visit Vermilion arrived on a rainy Sunday morning, December 8, 1901 from the "East and West Main Street line of Norwalk." This was actually a streetcar route operated by the Sandusky, Milan & Norwalk, which by 1901 was for all intents and purposes merged with the Sandusky & Interurban. Within days runs were being made from Lorain to Norwalk and by the end of the month the first through trip from Cleveland to Detroit was made. Service on the new Lake Shore Electric Railway had begun. East Side Stops From Lorain the Lake Shore Electric entered Vermilion alongside the Nickel Plate Railroad, pasing farms named for families such as Kishman and Baumhart, names well known and respected in Vermilion history. Stop 121, Kishman Beach, was at the point where Shepherd's Run (also known as Brownhelm Creek) empties into Lake Erie. Tall bridge abutments still exist here, but access is restricted. Stop 122 was at present day Helen Drive, just north of Lake Road. In 1917 featherweight boxing champion Johnny Kilbane established a "Recreation and Health Camp" here, encouraging parents to "start your boys up the road to health and sturdy, self-reliant manhood." Kilbane went on to a career in politics and in 1929 ownership of the camp passed to Max Ozer, who renamed it Camp Hakoah, a Jewish summer camp for boys. Max Ozer retired in 1933 and the camp once again changed ownership and name, becoming Camp Lester. Electric railway historian Robert Korach attended the camp in the early 1930's and recalls a horse barn at Lake Road for the campers' use, as well as hiking trips to Vermilion and Lorain where they would board the LSE for the trip back to camp. The original bunkhouses are still stand along the former Nickel Plate (now Norfolk Southern) railroad tracks and the LSE right-of-way can be seen alongside. Stop 123 was known as Loyola-on-the-Lake, a Jesuit summer retreat and school of science. Built in 1904 the impressive three story building existed quietly for thirteen years, carrying out its religious and scholarly purpose until it was destroyed by a fire in 1917. The property was held by the Jesuits of St. Ignatius High School and John Carroll University until 1992 and is now the site of the Vermilion Shores condominiums. Vermilion-on-the-Lake, at stop 125½, was founded by the Thompson & Sykes real estate company, who also developed the Lake Breeze neighborhood in Sheffield Lake. Originally known as the Werk Farm, the property was purchased in 1919 with the intent of building a summer resort for wealthy Clevelanders. A 10,000 square foot private community center known as the Vermilion-on-the-Lake Clubhouse was built just above the beach where it still stands today. The remaining land was divided into lots for summer cottages. In June of 1920 electric cars were chartered from Cleveland and Elyria to bring prospective buyers to the site. By 1938 the luxurious resort, with its beach-side boardwalks, city water supply, electricity and convenient transportation (both provided by the LSE), was nicknamed "the Atlantic City of the midwest." The resort became the village of Vermilion-on-the-Lake, a community unto itself, and continued as a summer destination and entertainment spot until its reputation began to fade in the 1950's. With the opening of Ford's Lorain assembly plant nearby in 1959 most of the cottages were coverted to year-round residences to house newly arrived workers. In 1960 the village of Vermilion became the city of Vermilion when it annexed Vermilion-on-the-Lake, greatly increasing its population. The LSE also stopped at a number of smaller beaches in Vermilion. Kishman Beach was at stop 121 on the far east side near Camp Hakoah. Stop 124½, Sunnyside Beach, was near present-day Woodside Ave. Stop 125, Sandy Beach, was at present-day Showse Park, and stop 127 was directly south of Elberta Beach, in the neighborhood of the same name. Diagonal Crossing The Nickel Plate Railroad and the Lake Shore Electric crossed Lake Road together at an awkward angle, known as "diagonal crossing" which became notorious as one of the most dangerous railroad crossings in the state of Ohio. Automobile drivers crossing the parallel tracks had difficulty seeing approaching steam trains and fast moving interurbans, resulting in many accidents. Calls to eliminate the crossing intensified in 1926 after three people were killed when an automobile was struck by an LSE freight car. A lack of funding, lethargic government action, and a dispute over how to eliminate the crossing (subway vs. bridge) delayed construction for many more years. Electric flashers and more visible warning signs were installed at the crossing in 1930 as part of a safety campaign, and construction of a bridge over the tracks finally began in the spring of 1937. By the time it was completed in 1938, however, the LSE was gone. The bridge was rebuilt to accomodate the current four lane highway and continues to carry traffic over the railroad tracks. Approaching downtown Vermilion the Nickel Plate passed under the New York Central railroad tracks while the LSE climbed the nearby terrain and crossed over the NKP tracks on a bridge. The original bridge was a wood trestle, replaced by a three span steel bridge in 1923. A bridge abutment is still barely visible on the east hillside above the railroad tracks. Linwood Park & Crystal Beach Stop 128, just east of Vermilion Road, served both Linwood Park and Crystal Beach, which were located just to the north between Lake Road and Lake Erie. This was also the location of the Linwood siding and a telephone booth used by LSE conductors to call ahead for their orders. A large pavillion was built here to shelter the crowds of people who rode the interurbans to and from the parks in the early days. A long sidewalk was built between the LSE stop and Linwood Park, a welcome convenience in the days of (often muddy) dirt roads. Linwood Park dates to 1880, when Nicholas Wagner opened a picnic grove on his property, known as Wagner's Woods, for social and fraternal outings. In November 1883 the German Evangelical Church purchased the land for their own summer recreation and religious meetings. Within a few years streets were laid out and lots divided. Over the ensuing years cottages, two tabernacles, a dance hall, a three story hotel, a dining hall, and bathhouse were all built. Concessions, vendors and amusements of many kinds created a lively atmosphere and for a few decades the park became very popular with both church members and locals in general. Unfortunately the outbreak of World War I gave rise to anti-German sentiment which caused a decline in the park's popularity. Many of the vendors were German craftsmen who closed their concessions and amusements. But the park survived and began to enjoy a resurgance in the 1960's. The hotel and many other structures are now gone but the cottages remain and the park is once again being appreciated for its unique charms. Adjoining Linwood Park to the east was Crystal Beach. In the 1870's George Shadduck established a public picnic grove and beach here named Shadduck's Grove. A dance hall, games, beer hall and baseball field were added later. In 1906 the park was purchased by George Blanchat, proprietor of Oak Point Park. When Shadduck's Grove opened for the 1907 season it was renamed Crystal Beach, reportedly after Mr. Blanchat's wife commented on the crystal-like quality of its sand. Mr. Blanchat's intent was to expand the grove into a full amusement park along the lines of Cedar Point. Numerous new attractions such as rides, a shooting gallery, ice cream parlour and a water slide were soon added. A sizable roller coaster, named The Thriller, was built in 1928 and for many years the beautiful Crystal Gardens dance hall hosted nationally recognized orchestras and singers. In the first two decades of the century the LSE was a primary means of transportation for visitors to the parks. Crowds in the summer sometimes necessitated two and even three car trains. Businesses and organizations often chartered LSE cars for company picnics and group outings. But like all facets of the LSE's operations, the automobile had a major impact. As roads improved and automobile ownership increased fewer people waited for the interurbans. By 1930 the farm between the LSE tracks and Crystal Beach was converted to a parking lot capable of holding 5000 cars. Soon stop 128 was virtually abandoned. The waiting station was torn down and the actual stopping point moved from Linwood siding to Vermilion Road. Crystal Beach continued operating well after the interurbans had disappeared, but changing times and competition from the much larger Cedar Point eventually caught up. In 1962 the buildings, rides and equipment were sold at auction and the land acquired by a development company which built the Crystal Shores apartments. |

run over the new LSE in December 1901. (Dennis Lamont) |

William Coen were one and the same. (Mrs. Walter J. Bishop collection) |

|

later Camp Hakoah, at stop 122. (Kilbane family) |

|

right-of-way. (Dan Brady photo) |

|

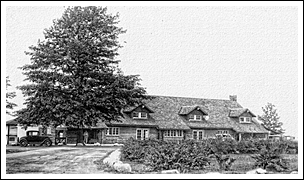

(Vermilion Views) |

|

(Albert C. Doane) |

|

(Pearl Roscoe photo) |

|

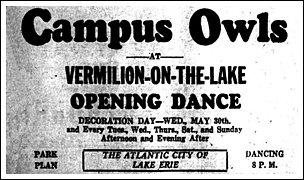

in May 1928. (Dan Brady) |

|

This was stop 125½ for Vermilion-on-the-Lake. (Todd Stoffer photo) |

|

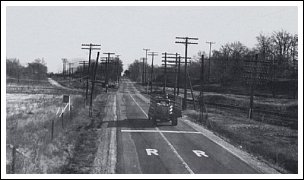

View is to the east. (Thomas Patton) |

|

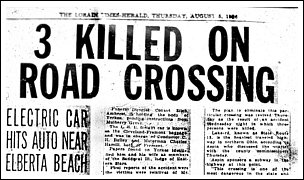

diagonal crossing. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

as part of 1930 safety campaign. (Karel Liebenauer) |

|

at diagonal crossing in 1938. (Dennis Lamont) |

at site of diagonal crossing. (Dan Brady photo) |

just east of West River Road. (Dennis Lamont) |

former NKP tracks. (Dennis Lamont photo) |

(Dennis Lamont photo) |

on this side of Vermilion. (Drew Penfield) |

Beach and Linwood Park to the north. (John A. Rehor) |

early 1900's. (Dennis Lamont) |

destination for LSE riders in its heyday. (Vermilion Views) |

(Rich Tarrant photo) |

Beach in the early 1900's. (Dennis Lamont) |

the road spelled the end of stop 128. (Dennis Lamont) |

ern Automatic company picnic in the 1930's. (Paul Eckler photo) |

quite rough in 1937. (Paul Eckler photo) |

that rode the LSE to the parks. (John A. Rehor) |

disused and the pavilion torn down. (Dennis Lamont) |

Vermilion Road sometime in 1937-38. (Paul Eckler photo) |

barely discernable in this 2005 photo. (Dennis Lamont photo) |

|

|

|