|

Settlement The primary figure of Monroeville's early history was Seth Brown, who arrived from Massachusetts in the spring of 1812. By 1815 others had arrived and established a tavern, dry goods store, and, most importantly, saw and grist mills powered by the Huron River. Vermont native James Breckenridge opened the first hotel in 1818. The village was originally named Monroe, in honor of President James Monroe (romantic legends that Seth Brown named it after Monroe, Michigan in honor of the bride and good fortune he found there during the War of 1812 notwithstanding.) The "-ville" was added upon establishment of a Post Office in the 1830s, as another Ohio town already had claim to the name Monroe. Monroeville remained primarily a farming village, with only a few small industrial operations in these early decades. Hauling grain to outside markets was extremely difficult until two important transportation improvements were created in the 1830s. A plank road was laid between Monroeville and Milan when the famous Milan Canal opened in 1839, but more important to future development were the railroads, the first of which predated the canal by a year. Railroads One may be surprised to learn that humble Monroeville holds the distinction of being the southern terminus of one of the very first railroads to operate in Ohio. The Monroeville & Sandusky City Railroad was chartered March 9, 1835, with Issac A. Mills of Sandusky as president, and Monroeville businessmen Edward Baker and George Hollister as secretary and treasurer, respectively. Construction was completed and operations began in 1838. The line only vaguely resembled what modern people would consider a railroad. The wide-gauge track was made of wood "mud sills" supporting widely-spaced ties. The rails were also wood with ribbons of strap iron spiked to the top edge on which the cars rode. Two horses harnessed in single file provided the motive power. Passenger cars were built on the pattern of contemporary horse carriages and accommodated about a dozen riders, while grain was hauled in gondola type cars covered with tarpaulins. The railroad's Monroeville station was located on Main Street, and served as both the passenger depot and grain elevator. A nearby hotel owned by Hollister (built on the site of Breckenridge's original hotel, which had burned down) was renamed the Railroad House. The tiny railroad fell into financial difficulties, however, and was sold to the Mansfield & New Haven Railroad on March 20, 1843. The combined companies were renamed the Mansfield & Sandusky City. The right-of-way was relocated a short distance to the west, but the new track was still of iron strap construction. The first steam powered locomotive, a wood-burner named "Mansfield," arrived on the property for use in the rebuilding. (Over the years, all the company's locomotives were named after towns along the line. A 4-4-0 type locomotive named "Monroeville" was delivered in 1864.) The full fifty-seven miles of the new line opened June 10, 1848. T rails finally replaced the iron strap in 1851, and another merger on November 23, 1853, resulted in the Sandusky, Mansfield & Newark Railroad. This company later became affiliated with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, which formally took control of the property in 1896. Monroeville was also on the route of the Cleveland & Toledo Railroad in 1851. (It is probably not a coincidence that the Mansfield & Sandusky City Railroad decided to upgrade their line with modern T rails the same year the Cleveland & Toledo was chartered.) The first passenger train operated over the Cleveland & Toledo originated at Monroeville and steamed to Toledo on December 22, 1852. Traffic between Toledo and the eastern terminus at Grafton commenced the following month, thus forging the last rail link between Buffalo and Chicago. In 1881, the Toledo division of the Wheeling & Lake Erie was built parallel to the LS&MS. Thus Monroeville found itself at the junction of three major steam railroads. Although the service and repair facilities of these railroads were all located in other towns, Monroeville's grain industry boomed thanks to rail service. The Heyman family was the local leader, operating both the Monroeville Roller Mills at the Huron River dam, and a grain elevator serviced by the B&O. The B&O also serviced the Boehm & Yanquell flour mills and the J.S. Roby malt house, while the Fish & Hills (later Horn Brothers) grain elevator was erected between the LS&MS and W&LE tracks at Ridge Street. Additional industries that arose in this period included the F.H. Mason & Sons Brick & Tile Works and the Edna Piano & Organ Company. Interurban Attempts In 1894, the pioneering Sandusky, Milan & Norwalk electric railway considered extending its line 3.5 miles to connect Norwalk and Monroeville. Consent was given from land owners along the route but no action was taken. It is unlikely the SM&N had the capital for construction, nor the ability to power cars at such a distance from their direct current power plant in Milan. The Monroeville Spectator reported that residents were amenable to the electric railway but also concerned it would carry Monroeville dollars away to Norwalk businesses. Locals suggested that the SM&N be extended to Bellevue in hopes that the resulting cross traffic would be more beneficial to their own town. This was likely another factor which discouraged the SM&N from pursuing a Monroeville extension. An attempt to fill this transportation void arose soon after, however, and is an intriguing and little-known interurban "ghost" story that is worth a closer look. Jonas "Clark" Rude was born in New York state in 1837. His family moved to Sandusky in 1840, where his father operated the Steamboat Hotel (later renamed the Veranda Hotel). Clark entered the business world as a bookkeeper for the Moss Brothers National Bank. In 1881, he was appointed collector of customs at Sandusky by the administration of President Garfield. Also that year, he was one of six incorporators of the horse-drawn Sandusky Street Railway, and in 1885 was named superintendent by company president J.O. Moss. Under Rude's management several new routes were built and the entire line was electrified in 1890. A year later he resigned his position in Sandusky and purchased the Mansfield Electric Street Ry., where he implemented extensive improvements. In 1892 he sold his interests in Mansfield and returned to the Sandusky Street Ry. He was also a director of the Sandusky & Columbus Short Line, and the Sandusky, Mansfield & Newark railroads, two other Moss investments. Given his résumé, there was little reason for skepticism when Rude announced his plan to build an electric railway connecting Sandusky, Monroeville, Bellevue, and Norwalk in late 1895. A petition in favor of the project was circulated among landowners along the proposed route, and a significant portion of the right-of-way was secured. Enough bonds were reportedly sold to fund construction of the railway, but no work took place. Early in 1898, the project was rechristened the Sandusky, Norwalk & Toledo, with a planned route of forty miles and two power houses, but again, no ground was broken. The final incarnation came in December 1899, when the Sandusky, Bellevue, Monroeville & Norwalk electric railway was incorporated. Rude's partner in the project was William Wallace Graham, one of Norwalk's wealthiest citizens. Graham began his railroad career with the W&LE in the 1870's and became an independent contractor in 1884. He built nearly all the bridges on the W&LE, furnished the bulk of their ties, and built another seventy bridges for the B&O. In 1890 he married his second wife, Clark Rude's daughter, Carrie. Franchises were granted by Huron County and the towns of Norwalk and Monroeville with the stipulation that work be completed by July 1900. Curiously, Rude and Graham contracted with an outside company to build their track. The Indestructible Roadbed Co. was founded in 1898 to build street railway roadbeds using a method patented by Peter Hevner in 1894. Rather than spiking rails to wood ties resting on a foundation of tamped earth and stone, the Hevner method used longitudinal, trapezoid shaped concrete stringers to which the rails were attached with bolts. (See illustration in ad below.) The company claimed this "far superior" system had been used successfully in Syracuse, New York and other cities, and to have millions of dollars worth of pending contracts, but corroborating evidence for these claims is conspicuous by its absence. The vice-president of the Indestructible Roadbed Co. was a Philadelphia businessman named J. Lancaster Dailey, while the secretary and treasurer was Charles McLain. Both men were among a group which arrived in Norwalk on June 8, 1900 to review properties and make arrangements to begin construction. Monroeville was to be the hub of the railway's three branches and the location of the power house and car barn. The village was especially optimistic over the potential benefits of the SBM&N and agreed to lease the company a plot of land for the powerhouse at present Milan and Hamilton Streets, near the Edna Piano factory, for ninety-nine years at one dollar per year. The first shovel of dirt wasn't turned until July 16, 1900, after the franchise deadline, but trust in the promoters was high and the franchises were all extended by several months. Work on the "indestructible" roadbed on Sandusky, Main, and Milan streets, as well as leveling the site of the power house were all begun in July. The next six months were the greatest period of activity. The power house foundation was complete by November and the brick and stone walls began rising shortly after. The concrete footings for a bridge parallel to Milan Street were done in December and masons began placing the stones for the abutments. As far as the local governments were concerned, this work demonstrated the company's commitment and the franchises were extended again, beginning a pattern that repeated itself over the next two years. Dailey was an immediate and enthusiastic proponent of the SBM&N, but there is no record of him having previous experience building or operating a railway. On October 22 he arrived in town claiming to have arranged the sale of $600,000 worth of bonds to a large eastern bank to fund construction. With him was a man named T.F. Brooks, purportedly an attorney representing the bond buyer. The project appeared to be moving forward as planned. A brief bio in a 1900 edition of the Philadelphia Times Sun, however, states that Brooks was actually council for the Indestructible Roadbed Co. All was not as it appeared. Trouble began to surface in January 1901, when several workers and sub-contractors filed suit for non-payment against the Indestructible Roadbed Co. Still, optimism did not waver. Rude and Graham were trusted locals, while the grand proclamations of Dailey and his associates were given credence based on their status as "Philadelphia capitalists." Throughout the year, Rude and Dailey gave assurances that the financial situation of the company was in order, the creditors would be paid, and work would resume shortly. What little work that did take place progressed irregularly and at a snail's pace. The only sections of track ever completed were within the city limits of Monroeville and Norwalk, apparently to satisfy franchise requirements and give townspeople a positive impression. Time and again company officials listed the building materials they had ordered and predicted the railway would be in operation within months. But the materials invariably went astray during shipping, were delayed due to shortages, or other assorted explanations. What materials did arrive were usually in quantities far less than originally stated. Meanwhile, the power plant sat empty and roofless, a symbol of the railway's unfulfilled promises. New assurances came on March 22, 1902 from chief engineer William Forsythe, who announced that the boilers, dynamos, and other machinery for the power house would be on site "next month." Furthermore, seven beautiful cars had been built, painted, and lettered for the company by the John Stephenson Company of New Jersey, to be shipped the following week. Four days later the Norwalk council extended the franchise yet again to June 1, 1902, on the condition that all local debts be paid by April 10. The newspapers reported that all claims by Norwalk creditors were settled (some at the last possible minute) but that the "pay car" was notably absent from Monroeville. They apparently did not notice the lack of machinery and car deliveries. The July 5, 1902 edition of Street Railway Journal proves the cars were indeed ordered and built, but clearly payment was never made. What became of those seven cars, as well as whether the boilers and dynamos were actually ordered, is unknown. In any case, no further work had been accomplished when the extended deadline arrived yet again, and the patience of Norwalk's council was exhausted. On the evening of July 1, 1902 they declared the SBM&N franchise forfeit and ordered the track and materials removed from the streets. By August the token workforce at Monroeville was gone. Early in 1903 rumors flourished that new financiers had become interested in the SBM&N. On May 2, 1903, Forsythe announced that Dailey and Brooks were no longer involved and that "new men with ample capital have become interested in the enterprise." On July 6 he revealed that the Elkins-Widener syndicate, the massively wealthy electric railway kings of Philadelphia, were the new backers. Forsythe arrived with a Dr. G.L. Lewis, representative of the syndicate, and set about paying old claims. By the end of the month it was stated that nearly everything required for the railway had been ordered. The Westinghouse Co. was engaged in working up an estimate for the electrical equipment, and the records of the J.G. Brill Co. show that an order for seven passenger cars and a single express car was placed on July 11, to be delivered between October 15 and November 1. The Sandusky B&O agent confirmed that thirteen carloads of rails had arrived, followed in the next few months by a carload of spikes and $8,000 worth of copper overhead wire. Then the bottom fell out once again. On September 1 1903, Charles McLain, secretary and treasurer of the Indestructible Roadbed Co. and the largest stockholder of the SBM&N, died at his home in New York. Despite the arrival of materials, no new construction had taken place, and for the second time an order for cars went unpaid. (Brill eventually found new buyers for the seven passenger cars they'd built. Two were sold to the Chicago & Indiana Air Line, a predecessor of the Chicago, South Shore & South Bend; two went to the Schuylkill Traction Company of Pennsylvania; one to the Chicago & South Shore, later Indiana Northern; and two to the Oregon Water Power & Railway Company. There is no further record of the express car, however.) Did McLain's death cause the Elkins-Widener syndicate to pull their support? In reality the syndicate was never actually involved. The Philadelphia Inquirer of December 19, 1903 reports that the Indestructible Roadbed Co. was placed in receivership and an injunction issued against company president George Hevener and manager G.L. Lewis, restraining them from selling any stocks, bonds, or property - the same G.L. Lewis who had appeared in Norwalk. Furthermore, Lewis was arrested in August 1904 for a wide variety of frauds, some of which hinged on portraying himself as an official of the Elkins-Widener syndicate. He was later sentenced to eight years in Eastern State Penitentiary. Amazingly, in May 1904, Forsythe claimed yet again to have new investors, but by then the public was deeply skeptical. The Monroeville Spectator, long an optimistic champion of the SBM&N, pointedly advised that he should stay out of town unless he could prove there was any serious possibility of the road being built. There is no report of Forsythe arriving in Monroeville again. In July 1904 the SBM&N failed to make the $1 lease payment on the power house property, whereupon the village began foreclosure proceedings. Despite the deceptions and ignoble end, the SBM&N was probably not intended as a fraud. In those highly speculative days of the first interurban boom there was no shortage of unscrupulous promoters who made investors' money vanish, but Rude and Graham were in all likelihood sincere in their desire to build the road. The honesty and sincerity of the Indestructible Roadbed Co. is a separate question. Why two highly experienced railway builders chose to so thoroughly entwine themselves with an unproven, out-of-state contractor remains a mystery. The $600,000 of bonds that Dailey repeatedly claimed he'd sold had indeed been authorized by the Commonwealth Insurance & Trust Co. of Philadelphia, but only $83,000 are known to have been sold. None of the SBM&N's promoters appear to have either suffered or profited much from the venture. Rude and Graham retired, living out their already comfortable lives with reputations intact. Dailey tried his hand at several other businesses in the Philadelphia area before spending his later years as president of a local lumber company. Forsythe continued working as a civil engineer in Philadelphia for many years. |

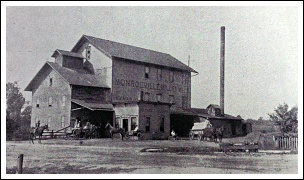

Subsequent dams and mills were built at the same site. This photo shows the Heyman mill circa 1900. (Drew Penfield) |

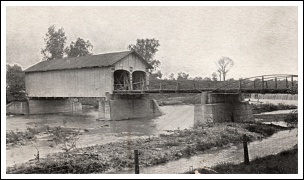

in 1836-1837. The landmark bridge was far too frail to support interurban cars and was replaced in 1910. (Drew Penfield) |

|

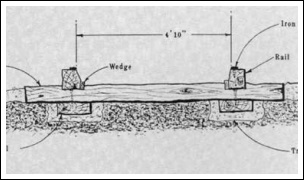

construction employed by the Monroeville & Sandusky City railroad from 1838-1851. (Drew Penfield) |

|

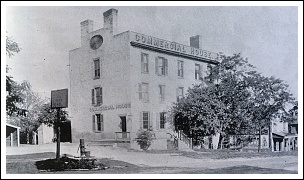

previous 1818 hotel. It was renamed the Commercial House by the time this photo was captured in 1896. (Picturesque Huron County) |

|

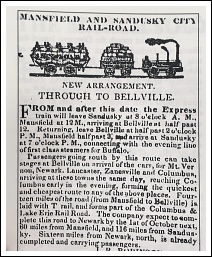

dusky City railroad, which had been extended as far south as Belleville. The ad illustrates the type of locomotives, freight cars, and passenger coaches then in use. (Robert Carter) |

|

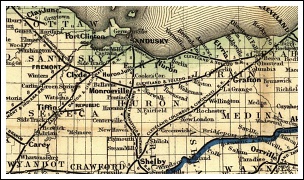

Mansfield & Newark Railroad, including a short branch to Huron. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

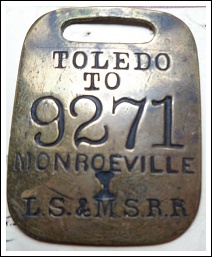

Southern used for baggage traveling betwen Toledo and Monroeville. (Drew Penfield) |

|

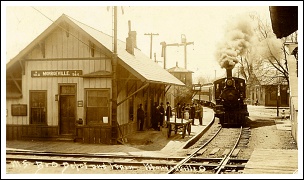

lines. In this 1910 photo a B&O train approaches from the south. The LS&MS depot is in the background at right. (Willis Leiter photo) |

|

Monroeville's leading flouring mill. (Norwalk Reflector) |

|

River dam, as it looked in 1896. (Picturesque Huron County) |

|

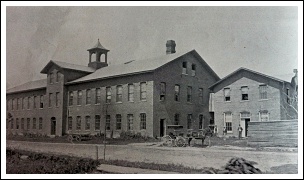

Monroeville. The SBM&N built their powerhouse near the Edna factory at Milan and Hamilton Streets. (Picturesque Huron County) |

|

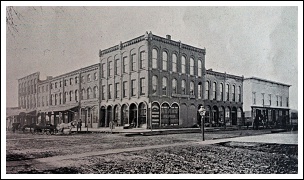

of Main and Monroe Streets, seen here in 1896. (Picturesque Huron County) |

|

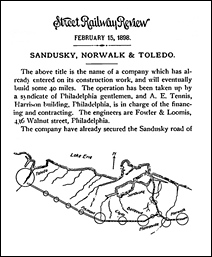

Norwalk & Toledo Ry. was an even more abitious proposal than both their first plan of 1895 and the SBM&N. (Street Railway Review) |

|

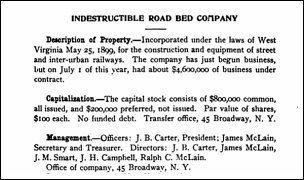

Industrial Securities for 1900. (Bradley Knapp) |

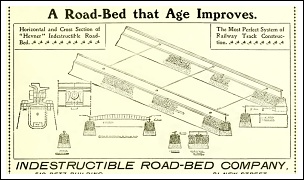

superior "Hevner method" of track construction. The few miles of such track built in Monroeville were never put to use. (Street Railway Journal) |

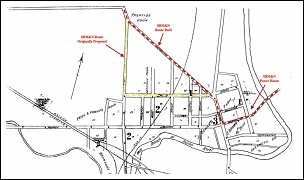

the route that was eventually built, and the location of the never-completed powerhouse. (Drew Penfield) |

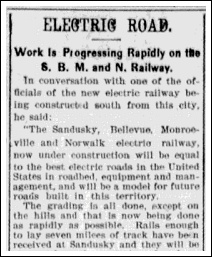

was typical of the grandiose promises made by the SBM&N promoters. (Sandusky Register) |

SBM&N, but ground to a halt six months later and never seriously resumed. (Norwalk Reflector) |

house was filed in December 1901 by the contractor who had built the structure and the company that supplied the materials, among others. (Norwalk Reflector) |

of the SBM&N. Even with work stopped and creditors seeking a lien, company attorney Brooks insisted that materials were coming and the line would be finished soon. (Sandusky Star Journal) |

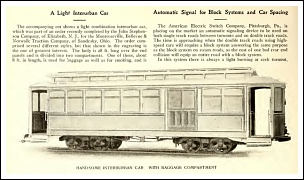

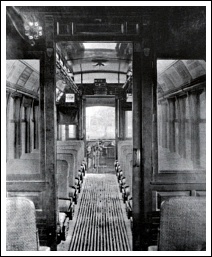

article on the cars built for the SBM&N by the John Stephenson Co. The railway had already lost its Norwalk franchise by the time the article was published, however. (Street Railway Journal) |

Elkins-Widener syndicate and assured locals that the SBM&N would be built quickly. He was sentenced for fraud in December 1904. (Norwalk Reflector/Camden Morning Post) |

the Indestructible Roadbed Co. for seven passenger cars, one express car, trucks, and electrical equipment. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania) |

railway never paid for them, and all were eventually sold to other railways. Chicago & Indiana Air Line #1 was one such car. (Pennsylvania Historical Society) |

rear of Oregon Water Power & Railway car 56, another of the Brill cars originally built for the SBM&N. (Richard Thompson) |

Monroeville Spectator, formerly an enthusiastic supporter, made this statement against further "hot air." (Norwalk Reflector) |

and most of the remaining materials were sold off by the sheriff throughout 1904. (Norwalk Reflector) |

|

|

|