|

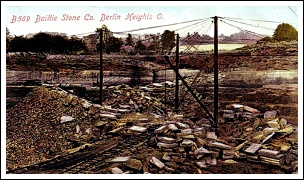

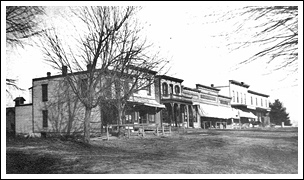

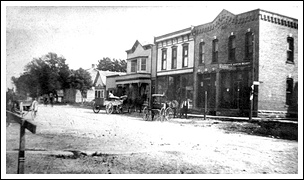

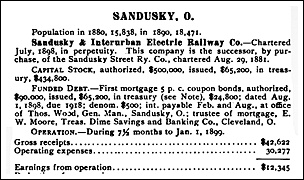

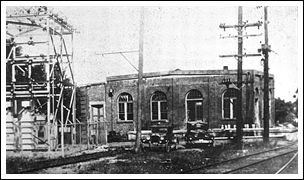

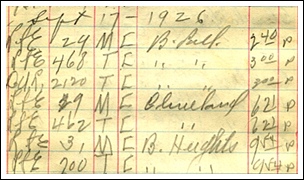

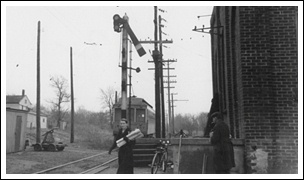

The village of Berlin Heights today is much as it was over one hundred years ago - a small, quiet town surrounded by farms and orchards. The population in 2000 was 685 people, only sixty more than were recorded in the 1900 census. But for a brief time in the early twentieth century - a period known as the interurban era - it seemed the future had arrived and Berlin Heights was poised to blossom into a modern city and transportation hub. Early farmers who came to Berlin Township in the 1800's, prospered thanks to the rich and varied soil, streams, and springs. Corn, wheat, and a variety of vegetables were the primary crops at first but the area soon made a name for itself as a major producer of apples, pears, peaches, grapes, cider and vinegar. Large stands of timber and easily accessible sandstone provided building material and early industries. The Berlin Fruit Box Company was founded in 1854 to make wood crates, barrels, and baskets for local farmers and orchards and is still in business today. Several small quarries provided stone for local building until a Canadian immigrant named George Baillie discovered an enormous deposit of sandstone just north of town. An adjacent gravel pit was of special interest to the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad which built a spur from its main line down to the gravel pit and quarry. In 1878 the railroad shipped over 400 carloads of sandstone from the Baillie Quarry. Interurbans Come to Town It was simply the luck of Berlin Heights' geographical location, however, that put it in the sites of the interurban companies just before the turn of the twentieth century. In 1899, a group of Michigan interurban promoters, backed by lumber and banking magnates Andrew and William Comstock, looked to expand their empire eastward. They chartered the Toledo, Fremont & Norwalk electric railway late that year and began construction in January 1900. That the TF&N would constitute the western half of a Cleveland to Toledo route was clear. Whichever Cleveland line reached Norwalk first would connect with the TF&N and could secure the best terms in a traffic agreement. The Cleveland, Elyria & Western, controlled by the Pomeroy- Mandlebaum syndicate, had built as far west as Oberlin, and was expected to be the TF&N's eastern connection. Pomeroy's typical practice was to back small upstarts seeking to connect two towns then absorb them into the system. In this case the Norwalk Gas & Electric Company was chartered to connect Oberlin to Norwalk. But the Everett-Moore syndicate, owners of the Lorain & Cleveland and Sandusky & Interurban, were not going to be shut out. The Sandusky & Interurban soon amended its charter to include an extension from the proposed mainline along Lake Erie south to Norwalk. Berlin Heights stood in the middle of both proposed routes and a slow race between the railways commenced. Planning the route was easy; the reality of building the lines was more complicated. Although construction on the Norwalk Gas & Electric began first in 1901, the project was held up for a considerable time by the need for a large bridge over the Vermilion River gorge near the town of Birmingham. And while the Sandusky & Interurban controlled the street railways of its namesake city, its eastward connection to Lorain existed only on paper. The minutes of the Berlin Heights village council, as reproduced in Faye Waldron's manuscript Berlin Heights Interurbans, give a view of the legal proceedings which brought the railways to town. In November 1900, Thomas Wood, manager of the S&I, and Horace Andrews, the company attorney, petitioned the Berlin Heights village council for permission to build and operate an electric railway through the village from north to south along the Ceylon Road, present State Route 61. Property owners along the proposed route were keen to the potential improvements and prosperity the interurbans could bring to town and signed petitions in favor of the route, even suggesting the railway be granted permission to use and/or cross any streets they wished. On January 23, 1901, the council granted the S&I permission to cut and grade a right-of-way at the north village limits but not yet lay ties and rails, presumably pending further approval of the route and conditions of the franchise, such as an ordinance passed February 19, requiring the railways to operate no less than six cars each way daily. The CE&W seems to have gotten an early upper hand, receiving the first franchises from the Erie County commissioners in January, and the Berlin Heights village council in February. But construction remained stalled and on April 30 council approved the S&I route and granted their franchise. The TF&N began regular service to Norwalk on May 1, 1901, but neither the CE&W nor the S&I were ready. The S&I had graded their route south from Ceylon but had not laid track. Meanwhile the CE&W was laying track in the streets of Berlin Heights but still had not bridged the Vermilion River. While the public perceived the two railways as racing to reach Norwalk, the real competition took place behind the scenes. Both Everett-Moore and Pomeroy negotiated to purchase the TF&N rather than simply connect to it. The ultimate victory was won in July 1901, when Everett-Moore struck a deal to purchase the TF&N. The railway officially changed hands on August 8, 1901, and became part of the Lake Shore Electric on August 29th. By the end of the year track was in place and LSE cars were running. Until the northern division through Sandusky was completed in 1907, all LSE traffic travelled through Berlin Heights. With the completion of the bridge at Birmingham in August 1902, the CE&W began regular service through the village as well. As many as seventy-four cars were rolling through Berlin Heights every day in these early years. Life in the quiet village changed abruptly. Commercial and residential electricity was available for the first time and the world seemed to shrink suddenly. As Faye Waldron summarized, "...down two country roads came the interurbans. Going south to Norwalk one line ran in South Street and the other through back yards! Some villagers could go to Birmingham, Oberlin, and Elyria off the front porch. Off the back porch was a ride to Huron and Sandusky. Both lines could get you to Cleveland and...opened vast opportunities in education, travel, career, medical help, and business expansion." A poem by Berlin Heights native and businessman Glyndon Crocker captured the excitement the interurbans brought to the village, reading in part: Seventy-four cars every day, Route & Station The LSE ran entirely on private right-of-way through the village. South from Ceylon the tracks followed the west edge of State Route 61 and crossed the Nickel Plate railroad at the intersection of Driver Road. A single ended siding existed just south of the Nickel Plate tracks, called Yale Siding in reference to stop 160 of the same name. Interestingly, at least one photo shows what appears to be an interchange track between the LSE and the Nickel Plate. This interchange does not appear in later diagrams and was possibly only in use during construction of the electric line. This crossing was the site of a collision between an LSE coach and a Nickel Plate freight train on the morning of October 3, 1902. Lake Shore Electric car number 1 was northbound from Berlin Heights, approaching the Nickel Plate crossing at about 15 miles per hour when the brakes failed. The car surged forward and struck a passing freight train. The interurban was knocked away but eight to ten cars of the freight train derailed and smashed through the Nickel Plate freight depot. All the interurban passengers were badly shaken and two were seriously hurt. Miraculously, both the Nickel Plate agent in the freight depot and the LSE motorman escaped with only minor injuries. Traffic on both the LSE and NKP was blocked most of the day as the wreckage was cleared. The Nickel Plate claims agent later estimated the cost of the demolished station and ten refrigerator cars at $200,000, not including cost of the damaged interurban car or injured passengers. After this accident, the Lake Shore was ordered to install derails on either side of the crossing. When open these would cause the wheels on one side of the car to come off the rail into the ballast and quickly stop. Cars could pass only after stopping for the conductor to check the crossing and manually close the derail. On September 29, 1903, Henry Everett's private car Josephine was carrying Republican candidates to Berlin Heights when the conductor forgot to stop and close the derails. The wheels of the car sank deep into the ballast, stopping it immediately. Another car was sent for the politicians while Jospehine was extracted. As the route neared the north end of the village the tracks veered away from the road, then crossed Mason Road, Mechanics Street, and West Main. A substantial brick substation, which doubled as the ticket office, passenger waiting room, and express office, was built on the south side of Main Street in 1903. The Higgins and Neff company of Bellevue were contracted to build the station after having built the substation at Vermilion. Both the Vermilion and Berlin Heights stations were patterned on the TF&N substation at Monroeville. The same design would later be adopted for substations on the Lorain to Cleveland Division. The Berlin Heights station endured a rough history. A fire on June 17, 1913 gutted the building, leaving only three quarters of the brickwork intact. A portable substation built on a flatcar was brought in to handle power while the station was rebuilt. A concrete dock to handle milk cans was added during this rebuild. A second fire struck within a few years, and a third on March 23, 1919. Barrels of lubricating oil stored inside the station fed the flames and caused over $15,000 in damage. The station was rebuilt yet again, this time with a flat roof. Various additions and outbuildings appeared over the years, and as with all LSE substations, the transformers were moved to a fenced yard outdoors in 1925. Station agents worked twelve hour days, seven days a week, including holidays. Each night, after passenger traffic had ended, the agent would shut down one of the two giant Westinghouse rotary converters for cleaning and brush adjustment, while the second converter provided power to the nightly freight run. Working around high voltage equipment certainly had its risks. On the morning of March 6, 1909, passengers arriving at the station to catch the first car of the day found station agent A.E. Lang lying dead on the floor. A hole burned through the sole of his shoe proved that he had been accidentally electrocuted. The occasional armed robbery was not unheard of either. On the evening of August 27, 1925, agent Albert Good was on duty when two men entered the station, held a gun to his head and demanded money. Mr. Good was unharmed and the men escaped in an automobile with about $20 in cash. Two sidings existed at the station for much of its life. One was a passing siding inline with the main track while the other was a single- ended spur behind the station. Various photos show work cars or ballast cars parked on this spur, but it also became handy for freight once the LSE entered that business. During the harvest season, a box trailer could be parked on the siding and loaded with farmers' produce throughout the day. At night the trailer would be hauled to Cleveland by the nightly freight run. Other freight, such as eggs, butter, milk, poultry, and express packages, was loaded on freight motors or combines from the station's dock. The Cleveland Southwestern had an identical freight operation on its own siding on East Main Street. In later years, after traffic over the southern division had waned, the passing siding was removed but the spur behind the station remained for freight, work cars, and transformer replacement. |

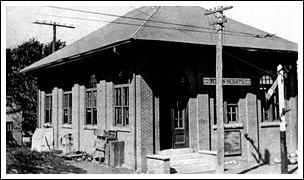

Both the Brill car and the station were relatively new. (Willis McCaleb) |

and traces of the railroad siding can still be seen in the Edison Woods metropark. (Drew Penfield) |

|

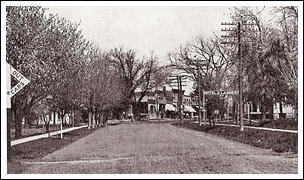

the arrival of the interurbans. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

(Dennis Lamont) |

|

(Street Railway Investments) |

|

commissioners in January 1901. (Cleveland Plain Dealer) |

|

first franchise in the village of Berlin Heights. (Elyria Reporter) |

|

between Birmingham and Norwalk wouldn't begin for another year, however. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

and Ceylon. Road at right is now Ohio Route 61. (Tom Bailey) |

|

Plate freight train on October 3, 1902. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

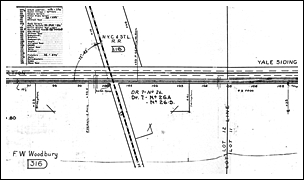

railroad, Yale siding, and derails installed after the 1902 wreck. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

is to the east. Station is just out of picture at right. (Berlin Heights Historical Society) |

|

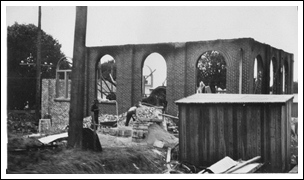

1913. View is to the northwest. (Berlin Heights Historical Society) |

|

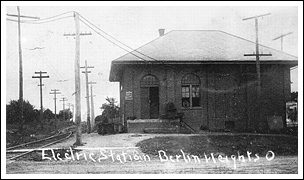

ticket office, express office, and passenger waiting room. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

(Dennis Lamont) |

substation building was being rebuilt. (Dennis Lamont) |

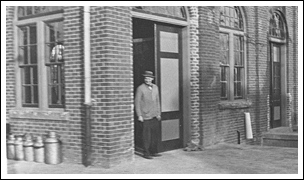

was added to handle milk cans. (Dennis Lamont) |

cans on the new loading dock. (Dennis Lamont) |

is northbound at the Main Street crossing in the 1930's. (Tom Patton) |

addition at left, and outdoor transformers (after 1925 Beach Park explosion.) (Dennis Lamont) |

the 1920's. A car loaded with ballast is parked on the siding. (Dennis Lamont) |

track and siding at the Berlin Heights station. (Drew Penfield) |

Heights with trailer 200 at 9:54 pm and arrived at Beach Park at 12:10 am. (Dennis Lamont) |

station dock in 1935. (Dennis Lamont) |

passing siding has been removed. House at right is still standing in 2012. (Dennis Lamont) |

disembarked westbound 157 at the station. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

|

|