|

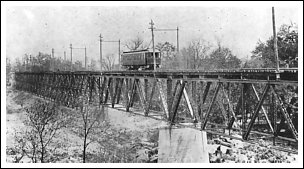

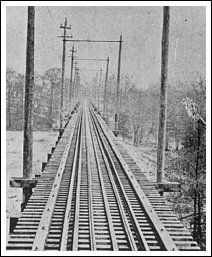

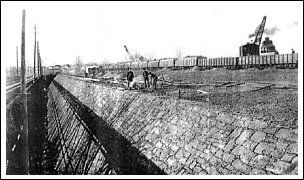

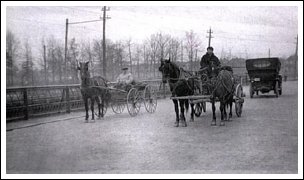

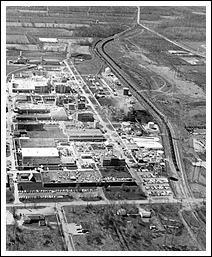

The Rise Of South Lorain To properly understand the AB&S one must understand the exponential growth of South Lorain at the turn of the century. The Lorain steel mill, built by Tom L. Johnson in 1894-95, was greatly expanded under the ownership of US Steel. By 1905 it included blast furnaces, a rolling mill, tube mill, ore docks, and the Lake Terminal Railroad, employing over 10,000 men in total. Plans were in the works to build a tin plate mill on land southeast of present East 36th Street and Grove Ave. Other industries included the Thew Automatic Shovel Works, American Shovel and Stamping, and various smaller foundries and manufacturers. There was also talk of American Steel and Wire relocated to South Lorain from Cleveland. Hundreds of new homes were being built in South Lorain, as well as accompanying businesses to serve the residents. The immense growth envisioned by the public, civic leaders, and industrialists cannot be overstated. An enormous transformation had already occurred and there appeared to be no end in sight. Three railroads (the B&O, Nickel Plate, and Lake Shore & Michigan Southern) already connected to the steel plant while three more (Wheeling & Lake Erie, Lake Erie & Pittsburgh, and the Lorain, Ashland & Southern) projected to reach the mill within a few short years. The Lake Shore Electric ran through downtown Lorain, while its rival, the Cleveland Southwestern, served Elyria, but the Lorain Street Railway was the only electric line in South Lorain. This was a booming period for electric railways. New lines were chartered and promoted almost daily, although most were never built. South Lorain's exploding population and business, and the lack of a direct connection to Cleveland, presented a perfect opportunity. An electric line connecting South Lorain to Cleveland had been proposed as early as 1900, and later became known as the South Lorain & Eastern. Right-of-way was surveyed and some land obtained between Rocky River and South Lorain, but for various reasons, including the problem of spanning the wide Black River valley, no construction took place and the plan was put on hold. The Lake Shore Electric received a great deal of Cleveland bound traffic from the Lorain Street Railway. A new direct route to Cleveland would have siphoned off this traffic and been a great blow to the LSE. Worse still was the possibility of the new line coming under the control of the Cleveland Southwestern. To prevent this the LSE needed to secure the Lorain Street Railway and build the connection themselves. The Lorain Street Railway was one of the few South Lorain properties still owned by Tom L. Johnson, who was then mayor of Cleveland and amenable to selling. Buying the railway outright presented a problem, however. In 1902 the Everett-Moore syndicate was over-extended and unable to pay multiple debts. The companies it owned, including the LSE, went into receivership. While the creditors were friendly and finances improved greatly by 1905, the LSE was still under the control of a banking committee that wouldn't allow the financial expenditure to buy the Lorain Street Railway and build a connecting line. To circumvent the committee Everett-Moore had two of their executives, LSE president Warren Bicknell and E.B. Hale, buy the Lorain Street Railway in their place and hold it as a separate company for the time being. The official change of ownership took place on March 11, 1905 and work to build the AB&S commenced that summer. Most of the construction was uneventful and devoid of engineering difficulties thanks to the flat rural land. A grade crossing with the Nickel Plate railroad was necessary south of Beach Park, and a double arch concrete bridge spanned the shallow French Creek. The biggest challenge, which had stymied the South Lorain & Eastern line, was crossing the wide Black River gorge at South Lorain. This was solved quickly, and at reduced cost, by employing a combination of wood trestle and two iron spans purchased secondhand from a steam railroad. Many railroads were then upgrading their bridges to handle heavier locomotives and longer trains but the old bridges were still structurally sound and more than adequate for interurbans. Exactly which railroad the bridges came from is unknown. On December 20, 1905, Lake Shore Electric car 70 made the first run over the new line, carrying dignitaries from Elyria to Cleveland. Regular scheduled service began the next day. Although the LSE route between Elyria and Cleveland was about eight miles longer than the CSW route, the faster LSE cars provided a comprable running time. Cars ran hourly between 6:30 a.m. and 9:30 p.m. with a stop at East 31st and Grove. South Lorain riders saw the greatest benefit from the new shortcut. Prior to the AB&S a trip from South Lorain to Cleveland required a three mile ride on the Lorain Street Railway to the loop at Broadway and Erie, then a transfer to an LSE car for the seven mile ride to Beach Park. The AB&S reduced this distance to five and a half miles. Direct Elyria to Cleveland service was apparently not a priority for the LSE and faded quickly. In less than a year the hourly schedule was reduced and through cars were replaced by a South Lorain to Avon Beach shuttle. The exact reasons for this are not known. It has been theorized that the LSE and CSW agreed to end some of their wasteful competition at this time, the LSE backing off the Elyria market while the CSW agreed to be less aggressive in Norwalk. It is also possible that Elyrians, still unhappy over the fare increase of 1901 and the LSE's refusal to lower fares after taking ownership, chose not to patronize the LSE in sufficient numbers and continued their established pattern of riding the CSW instead. The possibility that Elyria service was more of a side benefit than the primary purpose of the AB&S cannot be ruled out either. Just as South Lorain was rapidly becoming the center of Lorain commerce, rumors and machinations swirled around Oak Point, west of Lorain. It was widely believed and reported that a new industry would soon locate here and transform the mouth of Beaver Creek into a new harbor. While the LSE was enthusiastic about the propsect of new industry and population that would bring them new revenue, a harbor at Oak Point would require the construction of either a drawbridge or the relocation of the LSE tracks. A plan was made public in which the LSE main line would be diverted over the AB&S, pass through South Lorain, toward Amherst over private right-of-way, then turn north toward Vermilion, thus crossing Beaver Creek a mile south of Oak Point. Whether this plan was under consideration at the time the AB&S was built is unclear but intriguing, and could have been another expectation of the AB&S division's usefulness. The plan was rendered moot, however, when industry at Oak Point failed to materialize. For many years the AB&S also served as the only interchange between the Lake Shore Electric and its new Lorain subsidiary, as no interchange track existed at the Lorain loop until 1919. South Lorain had been established as a community for the workers of Tom Johnson's steel mill which had launched the sudden and dramatic industrial growth of Lorain and the prosperity of the street railway built to transport its workers. The mill was sold to J.P. Morgan's U.S. Steel in 1901 and plans were developed for an enormous expansion. Johnson had built the mill primarily for the production of rails, both standard railroad and the "Jaybird" rail for street railways. In 1905 the Lorain Tube Works began producing steel pipe and new coke ovens were built, but this was only the beginning. According to historian Dennis Lamont, the steel mill archives still hold blueprints and documents detailing a plan to expand the mill from 2 to 15 blast furnaces. Further plans included moving the American Steel & Wire plant from Cleveland to Lorain and building a sheet metal plant south of 31st Street. In the end, however, U.S. Steel created the town of Gary, Indiana for their new mill and the other plans never materialized. In the event they had, the potential of the combined Lorain Street Railway and Avon Beach & Southern would have been enormous, and the population would have flooded to the land along its route. This potential population increase may have been the motivation behind another unfulfilled plan involving the AB&S. A March, 1908 article in the Norwalk Reflector confirmed rumors that the Lake Shore Electric wanted to father a city at Beach Park, site of their station, power plant, and the northern terminus of the AB&S. The central location with railway service to Lorain, Cleveland and Elyria was touted as a selling point. Thus it appears that while writers are correct that the Avon Beach & Southern never lived up to its potential, most may not be aware of just how great that potential was. This would explain the Lake Shore's rush to build the AB&S so quickly after acquiring the Lorain Street Railway for so simple and unprofitable a reason as competing with one of the Cleveland Southwestern's routes. Following the Route Beginning at the Beach Park station the route of the AB&S is easy to follow with a few exceptions. Large portions of the right of way remain undeveloped and some construction which has taken place has left the route traceable even if the original roadbed no longer remains. Bridge and culvert remains can also be found. Much of the right-of-way has survived due to the area being predominately farmland which has left it undisturbed. However, as this farmland is converted to housing developments the right-of-way is being further divided and no doubt will disappear completely someday. From Beach Park a third track paralleled the Lake Shore mainline to the west, then made a turn to the south at Miller Road Park near the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co. coal conveyor. There are those who claim that original AB&S tracks survive in the present rail yard and are still in use. However it is more likely, as others maintain, that the original rails were pulled up during the construction of the coal conveyor and the reconstruction of the railyard which took place in the 1960's. Dennis Lamont recalls walking the rails before that time and seeing the original tracks with their electrical bonds still intact. Confirmation of any rails surviving to the present would be very difficult as access to the rail yard is now tightly restricted. South of the CEI rail yard is the wye track connection with the Norfolk Southern, formerly the Nickel Plate Railroad. This interchange was built in 1925 by the Avon Railroad division of CEI. A strip of dirt road through the middle of this interchange follows the path of the AB&S roadbed where it crossed the Nickel Plate tracks, then followed the east side of Miller Road. At Colorado Ave. the right-of-way continued south and crossed French Creek on a concrete double arch bridge. The area to the south was excavated during the construction of Interstate 90 then used by CEI as a fly ash dump. The dump trucks even used the old AB&S bridge to reach the dump site. Today All Pro Freight Stadium, a minor league ballpark, has been built near the site. Recreation Lane, the road leading to the stadium, follows the AB&S right-of-way, but the original arch bridge was replaced by a modern road bridge around 2009. The right-of-way can be followed again south of Interstate 90 and slightly to the west. Some of the roadbed in this area is threatened with new development and may already be gone as of this writing. One section appears to have been converted to a paved trail behind the new homes and is accessible from French Creek Road. South of the road more construction has eaten into the right-of-way, but the curve to the west is still plainly visible on satellite images. As the line curved to the west it crossed the tracks of the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern railroad's Lorain branch to the steel mill. This section is passable today because it is still used by the local farmer to access the surrounding fields. A box culvert over a small stream can be seen as well. The right-of-way is again cut by I-90 near Abbe Road, but can be picked up again from the old section of Abbe Road on the northwest side of the highway. Following the AB&S in this area can be tricky as it's easy to become confused with the path of the Lorain & West Virginia railroad. The steam railroad's tracks ran parallel to present day I-90, then curved north and east and entered a rail yard. The AB&S crossed these tracks as they curved, then crossed a small concrete bridge over Jungbluth Ditch. The small bridge still exists, as well as another used by the L&WV. The AB&S tracks veered to the north and ran along the south edge of the L&WV rail yard. In fact, in 1907 the Lake Shore reluctantly agreed to move their tracks further south so the L&WV yard could be shoehorned in. This was part of a failed scheme between U.S. Steel and the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad (parent of the L&WV) to monopolize rail traffic in and out of the mill. Evidence of the yard is easy to see today, even from satellite images, as it was used well into the 1960's. This area is now the property of the Lorain County Metroparks and part of the Black River Reservation. The AB&S then crossed East River Road just south of 31st Street before crossing the Black River. A section of the old 31st Street still exists on the east side of the river, and the AB&S was just south of that. Spanning the Black River was a challenge for the railway's builders in 1905 because of the wide gorge they were forced to cross. The easiest location for a river crossing to the north had already been claimed by the Lake Terminal Railroad and the steel mill was using the property just to the south for dumping mill slag. Later this mill slag and other material would fill in much of the river gorge giving the city a narrow spot to build the 31st Street road bridge in 1913. A single span over the wide Black River valley of 1905 would have been quite expensive and time consuming to build, so the railway used a combination of techniques (and some thrift) to get the job done. At the east end of the valley the railway built a wood trestle, then poured concrete piers, topped with a steel truss bridge. Reportedly this steel span was made up of two bridges that had been purchased from a steam railroad and reused by the AB&S, which was quicker and cheaper than building from new. Later the railway began efforts to fill in the wood section, a common practice at the time as a form of wood preservation. Filling a wood trestle was the cheapest and easiest maintenance solution. The efforts continued slowly for several years. Earth excavated from the 28th Street underpass, built 1913-1914, was dumped here as fill. Abandonement By 1924 the AB&S was seeing little traffic and hopes that it would fulfill its potential had long since vanished. On June 28th the deadliest tornado in Ohio history struck Lorain. Devastated along with the rest of the city were the power lines and poles of the Lake Shore Electric. Although damage was repaired and service restored on the mainline relatively quickly, the lines on the Avon Beach & Southern division were not a priority. Eventually the decision was made not to repair the lines at all, and the AB&S was finished. The following year the line was sold to the Avon Railroad division of the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company, which had bought the Beach Park resort two years earlier to build their new power plant. The Avon Railroad planned to use the entire line and connect with all the steam railroads serving the steel mill, including the Nickel Plate, Lake Shore & Michigan Southern, Lorain & West Virginia, and the Baltimore & Ohio by way of the Lake Terminal Railroad. In the end the Avon Railroad connected only with the Nickel Plate Road in Avon and the rest of the line to the south was abandoned. The rails and the 31st Street bridge were scrapped. The Avon Beach & Southern might have been a busy, profitable branch of the Lake Shore Electric, serving a giant steel mill, a town on the lake and all the businesses and residences between. In the end the opportunity to fulfill its potential never materialized and it became a nearly forgotten branch of the Lake Shore, itself undeservedly forgotten by too many. |

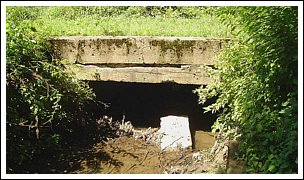

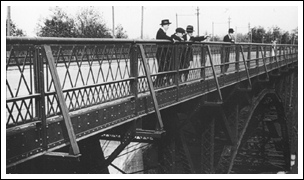

bridge over the Black River. (Drew Penfield) |

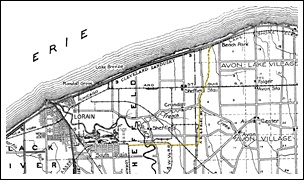

AB&S is highlighted in yellow. (Railsandtrails.com) |

|

network, and public services. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

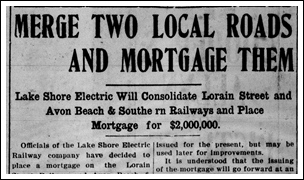

Lorain Street Ry and plans to build AB&S. (Drew Penfield) |

|

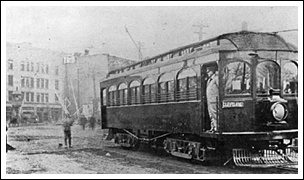

the first trip over the AB&S on Dec. 20, 1905. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

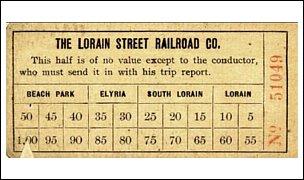

the AB&S and the renamed Lorain Street Railroad. (Dan Brady) |

|

to the Avon Beach & Southern division. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

in 2011. (Drew Penfield photo) |

|

when new in 1906. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

fly ash from the CEI power plant. (Dennis Lamont photo) |

new stadium and business park. (Drew Penfield photo) |

(Todd Stoffer photo) |

|

& West Virginia rail yard in 2009. (Todd Stoffer photo) |

|

farmer to reach his fields in 2010. (Todd Stoffer photo) |

|

days before 31st Street crossed the river. (Dennis Lamont) |

the bridge. (Dennis Lamont) |

of the bridge. (Dennis Lamont) |

AB&S trestle. (Dennis Lamont) |

is unloading mill slag on temporary track. (Dennis Lamont) |

AB&S bridge in 1913. (Dennis Lamont) |

(Dennis Lamont) |

the background. (Sheffield Village Historical Society) |

Street bridge. AB&S in background. (Dennis Lamont) |

under the AB&S wood trestle. (Black River Historical Society) |

Park, South Lorain and Elyria. (Dennis Lamont) |

ground blocks tracks at dismantled Black River bridge. (Ralph Sayles) |

they appeared in 1952. (Dennis Lamont) |

on east bank of Black River, 1978. (Dennis Lamont photo) |

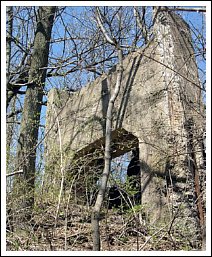

standing in 2008. (Sheffield Village Historical Society) |

AB&S pier in 2008. (Sheffield Village Historical Society) |

the AB&S switch, in 1926. (Avon Lake Public Library) |

AB&S right-of-way. Miller Road at top right. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

|

|