|

The town of Sheffield Lake has long been overshadowed by its larger neighbors, existing for many decades in a quiet space between the industrial might of Lorain to the west, and the mix of residences and industry in Avon Lake to the east. Although Sheffield was the first township organized after the creation of Lorain County in 1822, Sheffield Lake in its present form resulted from changes and divisions that began shortly before the turn of the twentieth century. Township land west of the Black River became the site of the Johnson Steel Company and was annexed by the city of Lorain in 1894, as was land west of Root Road. The village of Sheffield Lake was incorporated in 1920, but the needs and aspirations of the residents in the northern and southern parts of the village had begun to diverge. In 1933 they voted to separate, creating Sheffield Village south of Sheffield Lake. Although the Lake Shore Electric contributed to the growth of Sheffield Lake, modest as it was compared to other towns, no concentrated commercial or industrial center ever developed. The village was primarily one of dairy farms, cottage resorts, and residential neighborhoods during the interurban years, and the railway, which never had more than a string of flag stops across the village, was gone before any housing boom occurred. For these reasons Sheffield Lake is usually overlooked in any profile of LSE history. Even newspapers of the period usually substituted "east of Lorain" for the actual name of the village. But Sheffield Lake is still home to traces of the railway and was the location of events worth discussing. Lake Breeze The northwest corner of Sheffield Lake has become synonymous with the name of the first hotel in the area, The Lake Breeze House. It was built by Jay Terrell, who was originally from North Ridgeville, on the lake shore about 0.4 miles east of present-day Lake Breeze Road, and opened for business in 1873. Terrell was an amateur paleontologist who became noted for the fossils of a giant prehistoric fish that he discovered in the area in 1867, and which was named Dunkelosteus terrelli in his honor. His hotel included cottages around the main house, row boats for guests to launch from the sandy beach, and seventy acres of wooded property south of the hotel for hunting. The hotel became even more popular with the coming of the Nickel Plate Railroad in 1881, which made stops at many resorts along the lake. Carriage service was provided between the hotel and Lake Breeze Station, 1.3 miles away, and later to the Devonian Springs in Lorain. Ownership changed several times over the following decades. Between 1897 and 1903 it was owned by D.D. Lewis, manager of the Johnson Steel Company. It was purchased by the Redington Realty Company in November 1903, which announced plans for a new hotel building and larger, more modern resort. The exact fate of the hotel is unknown, but it was most likely torn down around this time. The planned resort was never built. A farm just east of the old hotel became the Lake Breeze Dairy, which operated from at least 1910 to around 1917. Little is known about this business, but the dairy's address was listed as stop 82 on the Lake Shore Electric Railway, at present day Sunset Ave. A large barn stood near the tracks at stop 83, and it is possible that the LSE hauled milk from this dairy to Cleveland, as it did at other locations. However, no records or photographs have yet been found to confirm this. In the 1920's the Thompson & Sykes real estate company promoted the Lake Breeze Allotment, a residential neighborhood on the southwest side of Lake Road and Lake Breeze Road. The convenient transportation of the Lake Shore Electric, which ran through the allotment, was one of several selling points used to entice buyers. The neighborhood was slow to develop, however, and the Great Depression prevented further growth until the post-war housing boom of the 1940's and 50's. In 1959 the Shoreway Shopping Center was opened at the southeast corner of Lake Road and Lake Breeze Road. Both the shopping center and some of the first homes built in the 1920's still exist. Early Incidents The Lorain & Cleveland Electric Railway began scheduled service on October 6, 1897, with cars crossing Sheffield Lake every half hour on their runs between the namesake cities. The single-track mainline and passing sidings were sufficient in those early years, but became a liability after the consolidation of the Lake Shore Electric and the corresponding increase in traffic. A couple notable accidents occurred at the Sheffield siding, which was located between present-day Buckeye Drive and Abbe Road. At 7:40 AM on December 13, 1902, LSE car 4, a Barney & Smith coach recently rebuilt for high speed service, departed Lorain headed east. The car had orders to wait at Sheffield siding for westbound car 57 to pass. As the car reached the siding motorman Bert Arnold applied the brakes, but the rails were icy and the car did not slow down. Motorman Searls, in the approaching car 57, could see that car 4 had passed the siding and was still rushing toward him. He threw his motors into reverse and jumped from his car. The two cars collided, and motorman Arnold, who had stayed at his controller, was pinned to the floor of the crushed vestibule. None of the passengers on either car were injured, but a fierce fire erupted which threatened to burn Arnold alive. Passengers Edward Dollar of Lorain and Frank Conrad of Rocky River freed the motorman after an heroic effort. The two cars were soon reduced to ashes, but motorman Arnold suffered only a burned coat and eyebrows. During the course of the same week, Arnold saw a young girl killed by another car, and a man severely injured. The three incidents in so short a time proved too much for his conscience, and he tendered his resignation soon after. A similar, but more serious, accident occurred at Sheffield siding on the night of September 3, 1903. Car 8, another Barney & Smith coach, left Lorain at 10:28 PM bound for Cleveland. In charge was motorman P.N. Weaver and conductor Edward Krueger. Only three passengers rode the car: William Aiken of Cleveland, Albert Gegenheimer of Vermilion, and LSE civil engineer William Minkler of Fremont. The car was speeding across Sheffield Lake at nearly sixty miles per hour as it approached the siding. Suddenly, the car was shoved into the siding, and before the motorman had any chance to reduce the car's speed, plowed into a string of steel coal hoppers which had been parked awaiting delivery to the Beach Park powerhouse. Conductor Krueger had his right leg broken and deep wounds to his thigh. William Aiken suffered a back injury and Albert Gegenheimer received a broken nose and cuts and bruises to his head. Minkler was thrown about the car, and serious internal injuries were suspected. Miraculously, motorman Weaver was the least injured of all, with only slight cuts, bruises. Aiken later claimed that conductor Krueger had taken control of the car while motorman Weaver went to smoke, which may have accounted for his escape from serious injury. All five men were taken to St. Joseph's hospital in Lorain via ambulances and a Cleveland, Elyria & Western interurban. Doctors did not expect Minkler or Krueger to survive, but their condition improved slightly the next day. Within a week Minkler was reported to be "getting along nicely." An investigation carried out by general manager Furman Stout and claims agent Harry Rimelspach determined that the switch into the siding had been carelessly left open by the crew of another car, most likely the one which had parked the coal hoppers there. Despite heavy damage, car 8 was repaired and put back in service. Head-on collisions and switch accidents were eliminated in 1906 when the LSE mainline between Cleveland and Lorain was double-tracked. An incident on February 1, 1904 taught one man, described by newspapers only as "an immigrant," a valuable lesson. The man had jumped onto the outside steps of an eastbound car as it left the Lorain station, apparently attempting to sneak a free ride to the next stop. Unknown to him the car was a Cleveland limited, which wasn't scheduled to make another stop until reaching Beach Park, nine miles away. Passengers discovered the man clinging to the outside of the car while rushing across Sheffield Lake at fifty miles per hour. The crew was alerted and the frightened, freezing man was rescued. The report says his hands were bruised and swollen from clutching the handrails and his face was blue from the cold. 103rd OVI Most LSE stops in Sheffield Lake served the small farms and residences which existed at that time. Stops such as Chapman's, Greene's, Austin Farm, and Rothgery, were all named for the owners of the farms the railway crossed. One of a few exceptions is the "103rd Encampment" at stop 71. The 103rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry was organized in 1862, consisting of approximately one thousand men from Cuyahoga, Lorain, and Medina counties who volunteered to fight for the Union army in the Civil War. After the war, the men gathered for annual reunions to maintain the friendships and camaraderie that had formed during the war. The locations for these reunions varied, and for several years they were held at Randall's Grove, a popular resort in east Lorain. As the years progressed, however, the veterans and their families sought a more permanent location and a place to preserve the history of their group. In 1907, they purchased four acres of land on the shore of Lake Erie in Sheffield township, at present-day 5501 East Lake Road. The 1908 reunion was the first held at the new site, and at first the attendees slept in tents, as they had elsewhere. In following years, however, cottages, a barracks, mess hall, and dance hall, were constructed. Today, some descendants of the original veterans live in the cottages year round and volunteer as groundskeepers and tour guides. In 1978, the barracks became the group's museum, displaying a large collection of Civil War artifacts. Cleveland Beach Although the planned successor to the Lake Breeze Hotel never materialized in the first decade of the century, a new cottage community was established shortly before World War I. By 1915 the property of the old Lake Breeze Hotel and the former Lake Breeze Dairy (and possibly other surrounding properties) were combined into the Cleveland Beach Allotment under ownership of the Lake Erie Beach Company. Details are sparse, but it appears that Percie Hills, a Cleveland car dealer and former state bowling champion, was a major figure of the company, as he was cited as the seller in the real estate transfers of many lots. Cleveland Beach was intended as a convenient country getaway, affordable to even modestly successful Clevelanders. Newspaper ads as far back as July 1919 advertised the allotment as the best of the country and city combined, 'not too far nor too near.' Lots were available for as little as $90 cash, or two dollars down and one dollar per week. A half mile sand beach provided for swimming, boating, and fishing open to all lot owners. Easy transportation was available via the LSE, with stops 82 and 83 directly on the property. The large barn at stop 83, approximately 50x100 feet, was converted to a dance hall with horseshoe pits, tennis courts, and a baseball field near by. One hundred cottages were built during 1920, and another hundred during 1921. A 1923 ad mentions stores selling provisions and lunches to the cottage dwellers. The Cleveland Beach dance hall grew in popularity with the general public as well. Newspaper ads in the late 20's and early 30's regularly announced which local bands and orchestras were performing at the hall for dancing on Wednesday, Saturday, and Sunday nights. The building also hosted other events, such as a large carnival held on October 4, 1930 to raise funds for the Sheffield Lake fire department. The popularity appears to have faded in the late 1930's, as did many other dance halls along the lake. Whether it was still used for regular dancing is uncertain, but it was put to other uses during World War II, hosting bingo games to raise money for civilian defense in 1942, and housing a makeshift assembly line for the American Specialty Company of Amherst in 1943. In July 1945 the 2.5 acres of property on which the dance hall stood was put up for sale. It was purchased by the Sheffield Lake Board of Education in September for the purpose of building a new school. The building was purchased at auction by Nick Kelling, who dismantled it, then reassembled it on his farm at the corner of Abbe and French Creek Roads where it served as a barn once again. In May 1955, the barn caught fire and was destroyed. Tennyson Elementary school now stands on the site of the dance hall, and a trace of the LSE right-of-way can still be seen behind the school. Some teachers and custodians at the school have reported ghostly sounds and apparitions of the long-deceased dancers who celebrated the summers over seven decades earlier in a converted barn. Many of the cottages built in the early days of Cleveland Beach still exist, and many more were built in the years preceding World War II. Most of these have since been converted into year round residences and are intermixed with homes built in more recent decades. The neighborhood north of Lake Road is now called Mizpah Beach, named for the Mizpah Country Club which was incorporated in 1922 and began leasing the beach in 1924. School Bus Tragedy Although head-on collisions of the kind described earlier were largely eliminated when the LSE double-tracked the Cleveland to Lorain section in 1906, by the 1920's another type of accident was becoming more common: interurbans and automobiles. Sadly, one of the most tragic accidents in the history of the LSE occurred in Sheffield Lake on October 23, 1924. That afternoon a school bus carrying thirty-five first and second grade students from Brookside school approached the LSE crossing at Bennett Road, now Abbe Road. At the wheel of the bus was thirty five year old Elmer Owens, who had been driving the bus on that route for at least a year. The children were singing, yelling, and making noise as they usually did. At the same moment, a westbound limited in charge of motorman R.C. Marshall and Conductor Lloyd Minor, was also approaching the crossing. The bus started across the tracks and almost immediately the big interurban car was bearing down. The motorman pulled his whistle in an emergency signal. The bus driver stepped on the gas in an attempt to clear the crossing, but it was too late. The electric car struck the bus, ripping off the back of the body and flipping it into the track side ditch, where it landed upside down. The interurban came to a stop some distance down the track amid a cloud of smoke and screeching wheels. Passengers ran to assist the wreck victims, as did Mrs. W.L. Clites, who heard the accident from the nearby Sunset Country Club. Clites carried the children to her nearby home and called for ambulances. A few children had been thrown from the bus, but miraculously they were relatively unscathed. Sixteen others were injured, some seriously. Worst of all, four children were killed, including the bus driver's own eight year old son, Albert Owens. The Lorain County coroner, the Ohio Public Utilities Commission, the Sheffield Board of Education, and the Lake Shore Electric, launched four separate investigations. Conflicting testimony complicated them all. Two questions lay at the center of the investigations: did the bus driver stop and look at the crossing, and did the motorman blow his whistle as he approached the crossing. LSE president Frederick Coen disclaimed any responsibility on the part of the railway, stating, "I am positive since I have heard the testimony of the witnesses that the school bus did not stop before going on the tracks." Parents of the children, however, professed their confidence in Owens and insisted that the motorman was speeding and had not signaled his approach. The possibility was also raised that a small waiting station between the road and the tracks may have blocked the view of the approaching car. During his testimony, Owens maintained that he had stopped, but also allowed that the noise from the children may have prevented him from hearing the whistle. After four weeks of investigation, the coroner declined to assign blame to any one party. Given the inconsistent witness accounts, he had no choice but to rule it simply an accident, albeit an avoidable one. The Public Utilities Commission found fault with the bus driver. Despite these rulings, no fewer than eleven lawsuits were filed by the victims families against the LSE, totaling nearly a quarter of a million dollars. The Sheffield Board of Education defended Owens, but also instituted a policy of placing an older student on each bus to assist the drivers at all railroad and interurban crossings. The policy remained in effect for fifty years. The board also repeated their demand that the deep ditch near the crossing be filled, citing it as a contributing factor in the deaths. The Public Utilities Commission finally mandated that electric flashers be installed at busy railroad crossings after a school bus was struck by a train in Berea in 1930. Bill Lang's Rescue The 1930's were a bleak time for the Lake Shore Electric and much of the nation. However, one incident in Sheffield Lake propelled the railway into national news for reasons that contrasted sharply with the school bus tragedy eight years earlier. On Wednesday, August 24, 1932, twenty-two month old Leila Smith wandered out of the yard at her home in the Lake Breeze allotment near stop 86. She found her way to the interurban tracks where she sat to play with her dolls. Meanwhile, LSE car 176, operated by motorman Bill Lang and conductor H.E. Rouzer, was speeding west at fifty-five miles per hour. As the car rounded a bend, Lang spotted the young child on the tracks about a thousand feet away. He opened the sand valve and applied the brakes hard, but could immediately see that the forty-five ton steel interurban would never stop in time. Acting quickly he climbed out of the cab and onto the front fender of the car which was still traveling in excess of forty miles per hour. With one hand on the car's bumper, and one foot wedged between the fender and the ladder, he reached forward and at the last instant grabbed little Leila, saving her from certain death. The car continued over one hundred feet further down the track before coming to a stop. Lang handed the child off to conductor Rouzer then climbed back into the cab and rushed the car to Lorain, where Leila was taken to St. Joseph's hospital. Her legs had been cut by the gravel ballast, and her hip was fractured from striking the fender of the car, but thanks to Lang's actions she was otherwise unharmed. Bill Lang was praised as a fearless hero by newspapers, neighbors, and Leila's grateful parents, but he remained steadfastly modest. He was awarded a Carnegie Medal for heroism and a special Interstate Commerce Commission award from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The rescue had caused Lang, 55, to wrench his back, which never fully recovered and led to his early retirement. In 1949 Leila Smith, then nineteen years old, was reunited with Lang at his home in Sandusky to personally thank him. They remained friends until his death in 1957. Ghosts of the LSE The growth of residential neighborhoods throughout Sheffield Lake over the last seventy years has obliterated most remains of the LSE. Remnants of right-of-way can still be found in some places along Hawthorne and Tennyson Avenues, especially near Tennyson Elementary School, former site of stop 83 and the Cleveland Beach dance hall. A number of small concrete bridges and culverts still remain, although on private property and hidden by foliage for most of the year. The intersection of Abbe and French Creek Roads, just outside Sheffield Lake, was the location of two LSE ghosts for a time. As described above, the former Cleveland Beach dance hall was moved to the Kelling farm and used as a barn until it was destroyed by a fire in 1955. On the opposite side of Abbe Road, was the final resting place of LSE car 178. It was sold to Nick Serbu of Lorain in 1939, and became part of the tavern operated by Mr. Serbu and his wife. It is believed to have been demolished sometime in the 1960's. |

has the approximate area of Sheffield Lake highlighted. (Drew Penfield) |

George Lampman, who ran the hotel after owner Mark Z. Lampman died in 1885. (Dan Brady) |

|

in the late 1880's. (Dan Brady) |

|

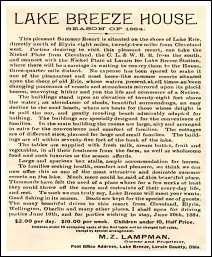

amenities at the Lake Breeze House for the 1884 season. (Sheffield Village Historical Society) |

|

skull of Dunkleosteus terrelli that he assembled at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. (Sheffield Village Historical Society) |

|

at Sheffield siding on December 13, 1902. (Plain Dealer) |

|

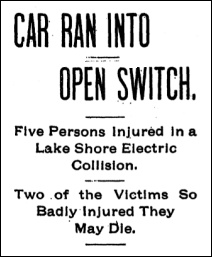

an accident and serious injuries on September 4, 1903. (Plain Dealer) |

|

and Abbe Road across from Erie Shore Landing apartments. (Drew Penfield) |

|

tracked in 1906. This view is likely from the 1930's. (Dennis Lamont) |

|

stop 71, when tents were still pitched next to new cottages. (Willis Leiter photo) |

|

a Civil War museum operated by descendents of the soldiers. (Dan Brady photo) |

|

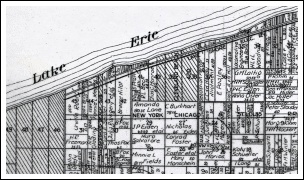

property of the Lake Breeze Hotel and Lake Breeze Dairy, on this 1915 tax map. (Drew Penfield) |

|

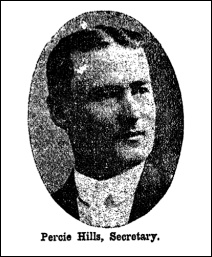

is believed to have been involved in the Lake Erie Beach Co. (Plain Dealer) |

|

already built on the property and extols its natural beauty. (Plain Dealer) |

|

a feature of Cleveland Beach that was heavily promoted, as in this 1923 ad. (Plain Dealer) |

|

Cleveland Beach from 1928 and 1931. (Drew Penfield) |

at auction in October 1945. (Chronicle-Telegram) |

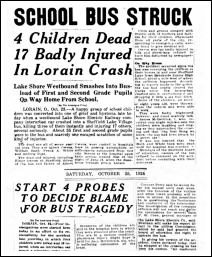

history, when a limited car hit a Sheffield school bus at stop 73. (Dennis Lamont) |

was involved in the deadly accident on October 23. (Sheffield Village Historical Society) |

Road, present-day Abbe Road, in March 2011. (Drew Penfield photo) |

View is looking west in 2011. (Drew Penfield photo) |

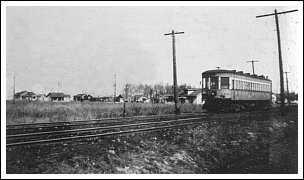

in Sheffield Lake, circa 1932. Note the electric flasher at right. (Ralph Perkin photo) |

west, probably sometime in the 1930's. (Dennis Lamont) |

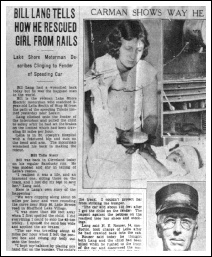

Leila Smith made big news in August 1932. (Dennis Lamont) |

from certain death on the tracks. (Harry Christiansen) |

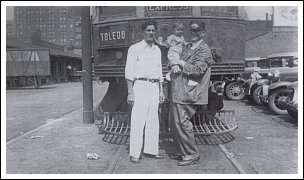

father at the Cleveland freight depot. (Richard Krisak) |

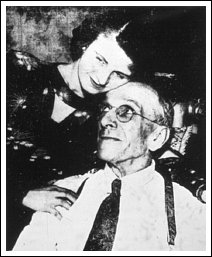

1949 and remained friends. (Dennis Lamont) |

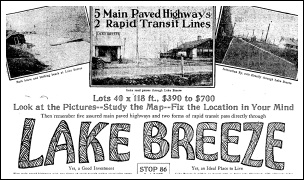

lists the LSE and the expected electrification of the Nickel Plate as selling points. (Dan Brady) |

of the new community, including convenient transportation. (Plain Dealer) |

while heading east on March 3, 1935. (Dennis Lamont) |

right-of-way looks today compared to the photo at left. (Drew Penfield photo) |

Kelling farm at French Creek and Abbe Roads from 1945 until it was destroyed by a fire in 1955. (Sheffield Village Historical Society) |

hall in 1949. Some have said it is haunted by the ghosts of dancers from decades past. (Drew Penfield photo) |

small bridges and culverts, such as this one near stop 71. (Drew Penfield photo) |

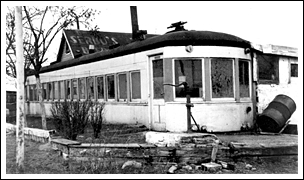

Creek Road and Abbe Road from 1939 until around 1965. (Dennis Lamont) |

|